Frank Wimberley Inducted into the Guild Hall Academy of the Arts

April 14, 2022 - Guild Hall Museum

April 14, 2022 - Guild Hall Museum

April 14, 2022

Christine Berry and Martha Campbell at the 2022 ARTTABLE Annual Benefit & Award Ceremony honoring Carol Cole Levin and Dr. Nicole R. Fleetwood.

Read More >>

April 8, 2022 - Howard University, Washington, D.C.

April 7, 2022 - Pollock-Krasner House

April 1, 2022 - Katya Kazakina for Artnet News

Drexler sold art to tourists for $50. Earlier this month, one of her paintings fetched over $1 million at Christie's.

What is going on there?

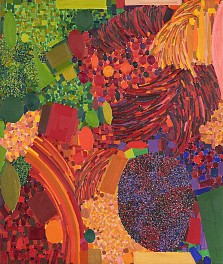

That’s the question market observers asked after a vibrant abstract canvas painted six decades ago by little-known artist Lynne Drexler soared to $1.2 million at a Christie’s off-season auction last month. More than 16 bidders propelled the work to 12 times its presale estimate of $40,000 to $60,000.

The price was mind-boggling for an artist who lived most of her life in obscurity, overshadowed, like many women of her generation, by a husband. She never had much of a career, showing here and there but rarely in New York City, whose hustle and bustle she eventually traded for the austere beauty of Monhegan, a small, rocky island off the coast of Maine.

There, amid harsh winters and touristy summers, Drexler spent her last 16 years painting daily, listening to the opera on the radio, and holding court at Jack Daniels-fueled salons. In the process, she filled her rickety white house with countless canvases. Her most inventive body of work—ecstatic abstracts created from torrents of vibrant brushstrokes, small and precise—was only discovered after her death, in 1999.

A second-generation Abstract Expressionist, Drexler’s star is rising as the contribution of female artists is being written back into the mainstream canon of art history (and the art market). The past few years have seen new records for Lee Krasner, Joan Mitchell, Alma Thomas, and Helen Frankenthaler, as well as Yayoi Kusama and Agnes Martin.

Drexler’s posthumous rise serves as a riposte to the idea that there are no more artists left to “rediscover.” Those who knew her just wish she could have been here to see it.

Before 2020, none of Drexler’s paintings had sold at auction for $10,000, let alone $1 million.

Something started to change that year, when a 1966 green painting fetched a quadruple-estimate $26,000 at Barridoff Auction in Portland, Maine. Since then, her work has consistently fetched five- and six-figure sums; most recently, $150,000 for PinKing 1970 at Barridoff on March 19. One of her paintings is now in the collection of John Legend and Chrissy Teigen.

“These women of the 20th century, who are related to the second movement of Abstract Expressionism, were so undervalued and under-circulated that it almost became a tempest when they started to be recognized,” said Michael Rancourt, who manages the Drexler estate, who has never before spoken to the press. Along with figures like Grace Hartigan and Yvonne Thomas, “Lynne is fortunate to be part of it.”

The record-setting Christie’s painting, Flowered Hundred (1962), was deaccessioned by the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, Maine. “It’s terrific that she’s finally getting her due,” said Christopher Brownawell, the museum’s director.

Drexler was born in 1928 in Newport News, Virginia and remained a Southern lady until her death. “She could curse like a pirate, but she judged people by their manners,’’ a friend recalled in a catalogue essay.

After attending the College of William and Mary, she came to New York in the 1950s to study with Robert Motherwell at Hunter College. She also took studio art classes with Hans Hofmann. She lived in the Chelsea Hotel and shared her downtown studio with painter Seymour Boardman.

In the early 1960s, she married fellow artist John Hultberg, whose large-scale Surrealist compositions won him the support of legendary gallerist Martha Jackson. She placed his works in top museums, paid for his (and Drexler’s) art supplies, and bought him a house on Monhegan Island, according to curator Tralice Bracy.

Jackson wasn’t particularly interested in Drexler’s work. “She wasn’t acknowledged as a painter, certainly not as a great painter,” Rancourt said. “She was the child in the corner, basically.”

Anita Shapolsky, a veteran New York art dealer, met Drexler while visiting Hultberg on the island in the early 1980s. She was unaware of Drexler’s Ab Ex phase. “She was a little angry at life,” Shapolsky recalled. “There were marital problems. At the time she was doing small paper pictures of nature for the tourists who came to the island.” Continue Reading

March 30, 2022 - Pollock-Krasner House

March 28, 2022

Nanette Carter: Almond's Artist and Writers Dinner

Almond Restaurant, Bridgehampton, New York

View Works by Nanette Carter

Read More >>

March 25, 2022 - Kim Doleatto for Sarasota Magazine

Architect Max Strang will guide a tour of Leedy’s architecture and share intimate stories about his time with the legendary architect

Gene Leedy, a founding father of the Sarasota School of Architecture, led a long and decorated career in midcentury modern architecture and beyond. He’ll be celebrated with a weekend tour of his work which will also kick off a three-week-long Leedy-focused exhibition. The event is led by Architecture Sarasota, a nonprofit dedicated to preserving the Sarasota School of Architecture style.

Although the bulk of Leedy’s work is in Winter Haven, Florida, where, in 1954, he moved his practice, Leedy started his career in Sarasota and left a lasting legacy.

At just 16 years old, he enrolled at the University of Florida and graduated with a degree in architecture. He then moved to Sarasota and worked under the tutelage of Paul Rudolph, an internationally acclaimed architect and a founder of the Sarasota School of Architecture style that emerged in the 1940s. Also called Sarasota Modern, the style is known for its Florida-sensitive design that often incorporates what were at the time avant-garde elements, like sliding floor-to-ceiling glass doors, roof overhangs to increase shade and expansive living areas that encouraged air circulation before many homes had air conditioning. It was a mindset that nurtured innovations in engineering, displayed in Leedy’s approach to his projects.

He’s best known for his use of precast concrete and double-T shaped beams, at the time engineering marvels that allowed for strong, lofty, large spaces like the 9,000-square-foot president’s residence at the University of South Florida in Tampa he designed in 1990. Leedy applied the same new wave of thinking when it came to his residential works.

“He designed modular and scalable homes that could easily be added to, so a couple could have a starter home that could grow. Some of his houses are still on Drexel Avenue in Winter Haven,” says Architecture Sarasota executive director Anne-Marie Russell. “Many still don’t have air conditioning because they worked so well with his passive system for shading and cooling.”

In Sarasota, Leedy designed Brentwood Elementary School in 1958, the House for Contemporary Builders in 1950 and two residential projects. One of them, the Solomon Residence & Studio, on Big Pass on Siesta Key, was built in 1970 and will be highlighted at the exhibition.

Syd Solomon was an abstract painter, and the home served as the site of Sarasota’s “beach culturati,” a subtropical salon where artists, writers, intellectuals, scientists and playwrights gathered. “That house became the location of Sarasota’s brain trust and shows how great architecture can create a platform for creativity,” says Russell. “It did what great architecture always does—inspires new ways of thinking, being and living.” Continue Reading