Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: Interview with Bentley Brown

August 25, 2022

This week, we sat down with Bentley Brown, artist, curator, and art historian, for an intimate perspective on the work of his father, Frederick J. Brown (1945–2012), whose art joined the MFA's collection earlier this year. We loved Brown’s wide-ranging, galaxy-inflected paintings when we saw them in New York at Berry Campbell gallery last fall and we’re thrilled to share with you a little about his art here.

The acquisition of Brown’s work formed an integral part of an initiative to broaden the narratives of abstract painting the MFA's collection can tell, made possible by Elizabeth and Woody Ives and in recognition of their critical contributions to the contemporary collection over decades. We are indebted to their support and generosity.

---

We know and admire Frederick J. Brown’s practice, but how would you describe it in around three sentences or so?

Fred Brown is an American painter whose work included abstraction, figurative expressionism, and portraiture. Born in Greensboro, Georgia and raised in Chicago, he drew from sources rooted in African-American culture in a practice of visual storytelling that sought to highlight mastery present in the Black communities in which he was raised. A lot of his motivation stemmed from the desire to see Black culture be venerated as a foundational part of American culture and the avant-garde. Brown came to prominence as a pioneer of New York’s downtown art scene of the 1970s and ’80s; his loft at 120 Wooster Street was a center for that scene, modeling itself after loft jazz alternative spaces.

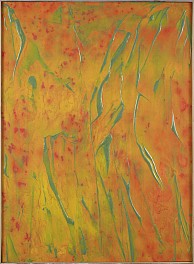

The MFA recently acquired Brown's painting, Untitled (1972). Could you share a little about its place in your father’s work?

When my father was making this piece he was living on the Bowery, having lived at jazz musician Ornette Coleman’s loft for a brief period. During this time he was exploring techniques in enriching color, creating depth through staining, and creating textural and sculptural qualities. My father was developing this work alongside fellow painters Frank Bowling and Daniel LaRue Johnson, who were exploring similar questions to push the boundaries of abstraction. They and others working in this vein wanted to see how far you could push the materials, to create work that was all-encompassing, that could reflect feeling and tell a story.

Our team was fascinated to learn about Brown’s work for the Adler Planetarium in Chicago. Could you tell us a little about that?

In 1971, my father began a correspondence with the Adler Planetarium. He wanted to create depictions of the Milky Way galaxy and wanted images as a reference point; the image of the galaxy remained a constant throughout his abstract work. He and the Planetarium staff stayed in contact throughout the 1970s; his painting Milky Way (1977) is on view there today. An important part of this was that the Adler Planetarium pictured the stars from the perspective of Chicago’s night sky. Today in Chicago it's almost impossible to see the stars, and that's a huge part of this series, my father as a young man in Chicago (and New York) imagining, dreaming of and for stars.

Anything we missed?

I’d like to expand a little on my father’s influences. In Chicago he was in the middle of all of these incredible focal points of Black music: blues, gospel, avant-garde jazz. Music was really a vector through which my father created his work. It was the musicians that brought my father to the Downtown New York scene.

Family influences shaped his aesthetic sensibilities, too. He cited my grandmother’s work as a Venetian pastry chef as a great influence. He would say that the paint had to be thick like the frosting my grandmother would make. The steel mill was another influence: his stepfather worked there, and my father did too for a period of time, as a safety inspector. The bright oranges and yellows of the smoldering metal and ingots appeared in so many of his works including the Untitled work acquired by the MFA.

Are there any artists, writers, or others working in the arts –– past or present –– whose work you would like to share and make readers aware of?

I’d like to list the creatives who were a part of the 120 Wooster Street Collective my father founded and its milieu. It is my duty to share this knowledge, to continue to say my father’s name and the names of all of those he labored with, because so easily we forget the immense contribution of Black artists in forging new points of access for creation and creativity.

Visual artists

Daniel LaRue Johnson, Virginia Jaramillo, Anthony Ramos, Frank Bowling, Bill Hutson, Gregoire Muller, Edvins Strautmanis, Algernon Miller, Ellsworth Ausby, Joe Overstreet, Al Loving, Ed Clark, Peter Bradley, Gerald Jackson, Jack Whitten, Romare Bearden, Willem De Kooning, Kapo, Milton George, Anthony Barboza, LeRoy Woodson, Ralph Gibson, Frosty Myers

Multidisciplinary artists

Malcolm Mooney, Megan Brown, Felipe Luciano, Gylan Kain, Claude Lawrence, Jean-Claude Samuel

Musicians

Anthony Braxton, Henry Threadgill, Art Ensemble of Chicago, Kunle Mwanga, Ornette Coleman, James Jordan, Revolutionary Ensemble, James “Blood” Ulmer, Charlie Haden, Sam Rivers