Jill Nathanson of Berry Campbell reviewed by Piri Halasz for the New York Observer

June 9, 2015 - Piri Halasz for New York Observer

Reports of the death of painting have been greatly exaggerated. Not least, its survival is due to artists like Jill Nathanson, whose current show at Berry Campbell combines traditional approaches with new technologies to create paintings that could only have been made in the 21st century.

“Jill Nathanson: Fluid Measure” (through June 27) is innovative in another way: it features 16 abstract paintings whose gossamer floating shapes and palely lovely colors might be called “hedonist” by those overly-conscientious critics who may feel either guilty or embarrassed about praising paintings whose sole purpose is to give pleasure by looking marvelous, or whose creator hasn’t chosen to present art that’s useful or conveys messages.

A part of my response may be due to the fact that, when I stopped by to see the show, I found the artist, who I first met many years ago at a Greenwich Village solo exhibition of her work, present. We got into a conversation about her materials and techniques that better enabled me to appreciate the uniqueness of her approach.

Nathanson’s shapes are bounded by edges that are sometimes straight, sometimes jagged, and occasionally rounded – all within the same picture. They look like pieces of paper that have been cut or torn, nor is this by chance. Rather, it’s because they’re based upon collages that constituted the preliminary studies, or modelli, for the paintings.

Each painting in the show went through at least three stages. First came the modello, made from cut or torn pieces of what are known in theatrical circles as “gels.” Gels are paper-thin transparent colored sheets of polycarbonate or polyester that project color when placed in front of lighting fixtures or windows. They are used, for example, in theaters to create colored spotlights, and are sold through theatrical lighting suppliers.

The second stage was to translate this modello into a smaller painting, which then became the basis for the larger, final one. As the original collage was made from transparent gels, its composition could incorporate some or even all shapes that, instead of being placed next to each other, overlapped. This meant that the shapes underneath remained visible and altered the color of some of the superimposed shapes.

All very well, you say, but what’s new about that? Making smaller, preliminary modelli goes right back through the ages, probably to the 14th century in Europe (though the 17th century modelli made by the Italian baroque sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini are particularly prized).

The difference here is that Ms. Nathanson’s modelli were made from transparent gels, and until very recently, no paints appear to have been made that would convey the same impression of transparency on a panel or canvas. Enter here those masterly paint manufacturers, Golden Artist Colors of New Berlin NY, who since 1980 have been creating a vast range of paints and other artist supplies which have enabled painters of every variety to achieve new and ever more wonderful effects.

From Golden Artist Colors, Nathanson has been obtaining not only oils and acrylics to create her paintings, but also a paint that the checklist at the gallery calls “polymer,” and that is mostly responsible for the elegant, fluid transparency which so distinguishes these paintings.

I wanted to use the brand name that corresponded to this miraculous “polymer,” so I looked at the Golden website. As I couldn’t find anything there that looked right, I called and learned that Nathanson uses “various pouring mediums” from the “custom lab” at Golden, where they prepare materials for individual customers. Such paints aren’t listed at the website nor are they available commercially. The pouring mediums that Nathanson employs have only been available since around 2010.

There you have it: the 21st century technology that makes possible the advanced pictures which Nathanson arrives at. Consulting my reviews of her last two shows (in 2010 and 2012), I find that she was already using these polymers then, but in the intervening period, she has learned to handle them far more effectively. At present, she relies upon her preliminary studies only up to a point, but sometimes edits unnecessary details out of them for the final version and/or experiments with freely-flowing, more accidental pourings.

For me, the best paintings in “Jill Nathanson: Fluid Measure,” are, on the whole, the larger and simpler ones, those which incorporate only a limited number of colors. The most complex and ambitious of these is In Fluence (2014). Situated in the front space of the gallery, it has cloudy sky blues in the upper left part of the canvas, deep red sweeping on the lower left, tans in various shapes in the upper right, and greens on the lower right with touches of cream.

Brass Instrument (2015), which hangs in the gallery’s central space, is quite powerful. In my discussion with the artist, she emphasized how she likes to get a dialog going between different corners or sides of a painting, but in this case, I was more aware of its delicate, gauzy central element – a broad, vertical and freely formed rectangle, with overlapping, transparent areas within it of tan, mustard and pale lime.

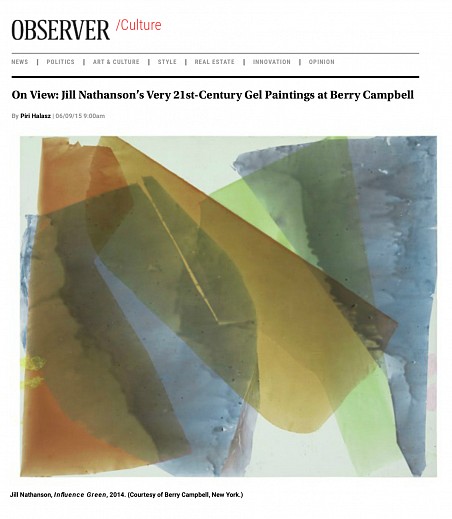

Best of all is Influence Green (2014), though it hangs in the back space of the gallery. It works best because the degree of saturation is most even: every element is equally luminous and bright. And it’s a grandly simple, truly classic composition with only two major components. On the upper left are two broad, diagonal light browns, slicing down diagonally and superimposed upon upstanding verticals of light blues and green. Small top and bottom areas are covered with thick white acrylic, no color at all here to distract the eye from the magnificence of the picture’s luminous centrality.

Back to News