Review on Walter Darby Bannard | Minimal Colorfield Paintings

June 3, 2015 - Phyllis Tuchman for Artforum

Walter Darby Bannard made a big splash with the abstractions he painted following his graduation from Princeton University in 1956. In the mid-1960s, his work, which featured, in Bannard’s own words, “plain, simple, symmetrical in-your-face color,” was included in historically important group exhibitions such as “Post-Painterly Abstraction” (1964), and “The Responsive Eye” (1965), organized, respectively, by critic Clement Greenberg and curator William C. Seitz.

A dozen or so canvases from 1958 to 1965 that were on view recently at Berry Campbell made it clear why Bannard, who is now eighty, was selected for these shows. Even back in the day, the emergent artist’s Minimalist compositions must have seemed timeless. These are, to be sure, smart paintings. And while it’s tempting to raise the specter of formalism today, it’s perhaps more apt to suggest that the nearly five-foot-square canvases call to mind a foreign language that’s almost been forgotten.

When Bannard briefly moved to New York from New Jersey, the so-called Tenth Street touch, characterized by overwrought, muddied paintings by a second generation of Abstract Expressionists, was flourishing. This Ivy Leaguer, however, was more enthralled by the art of the first generation, which he had the opportunity to see in depth. “The New American Painting” was on exhibit at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and Greenberg was behind solo shows mounted farther uptown at French & Co.

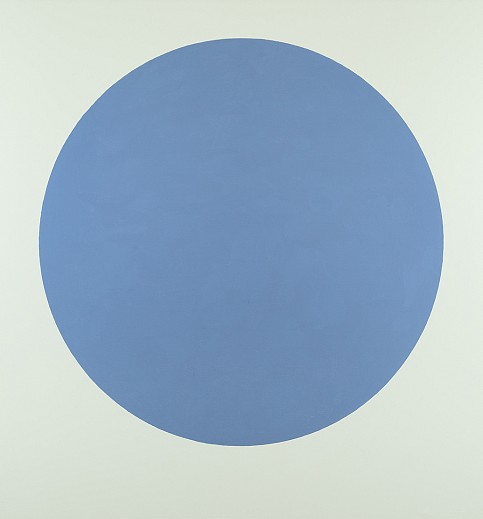

Bannard was influenced by Clyfford Still, though you’d be hard-pressed to make this connection if he didn’t make it himself; because Bannard worked with smaller canvases and preferred smooth to textured surfaces, his debt to Still is hardly obvious. But take a look at Truk, 1958, seen at Berry Campbell. Its cool tripartite composition—comprising an irregularly edged black mass, a wide swath of green, and a small red square—calls to mind a deconstructed Still. Bannard’s palette here is darker and stronger than anything that came after it. His subsequent canvases are sparer, understated, and unassuming. Elemental geometric forms—a large disk or a somewhat smaller rectangle—are the only elements that occupy his monochromatic fields. And then there are the “band” paintings, in which a much broader, unembellished field is framed by a thin strip of color.

The bands, circles, and rectangles tend to be shiny and reflect light, while the other parts of these canvases are covered with matte paint. Bannard mixed pinks and beiges as well as light blues and greens with lots of white. These colors are still radiant. And the artist’s pale palette is as uniquely personal today as it was fifty years ago. You can’t even apply a name to his hues.

Still, there’s something vaguely familiar about Bannard’s paintings from 1958 to 1965. In the April 1966 issue of Artforum, Rosalind Krauss saw a connection between Bannard’s work from this period and Morris Louis’s first burst of Unfurleds. But it’s more recent art that came to my mind. Having spent many hours sitting in lots of James Turrell’s sky spaces, I would hazard that both artists want us to relish color in similar ways, focusing the viewer’s attention with as little distraction as possible. It’s just that Bannard’s palette is static and immobile.

Bannard’s art had a very different lineage during the years when he first began exhibiting. His forthright canvases were shown alongside sculptures by Carl Andre, Donald Judd, and Robert Morris in the landmark 1965 “Shape and Structure” show at Tibor de Nagy, and in the company of Dan Flavin, Sol LeWitt, and Robert Smithson at galleries such as Kaymar and John Daniels. That same year, when Bannard introduced smaller, more irregular, multipart geometric shapes in canvases such as Seasons #1, he was able to apply many more colors to his canvases. Soon afterward, he abandoned the Minimalist vocabulary. By then, he was again living in Princeton, had become a contributing editor of Artforum, and was on the way to addressing other color issues in gestural abstractions executed in acrylics and gels.

—Phyllis Tuchman

Back to News