The New York Times | Out of Obscurity, Lynne Drexler's Abstract Paintings Fetch Millions

October 24, 2022 - Ted Loos for The New York Times

After a derailed career, Ms. Drexler became a “hermit” painter on an island. Decades later, piqued public interest can earn her work seven figures.

When two paintings sold for far higher than their estimates at auction last spring, by an artist very few people had ever heard of, a signal pierced the art market: The artist, Lynne Drexler, might merit more attention today than she ever received in her lifetime.

Both works are mosaiclike fields of bright colors. “Flowered Hundred” (1962) was estimated to sell at Christie’s New York for $40,000 to $60,000. It sold for just under $1.2 million in March.

The iron was hot; a couple of months later, some 20 buyers scrambled for “Herbert’s Garden” (1960) when it came up for auction for $70,000 to $100,000. It sold for $1.5 million.

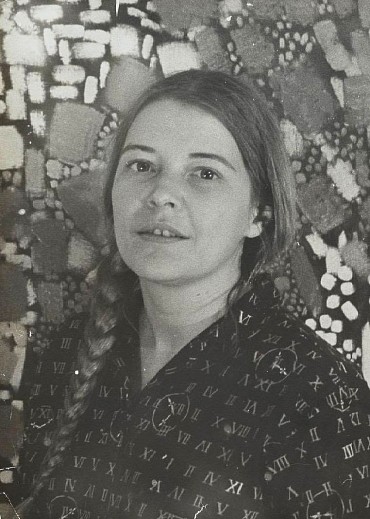

Ms. Drexler (1928-99) began with a promising career in the New York art scene — one reviewer compared her work to van Gogh’s — but she spent the last decades of her life as a self-described “hermit” on Monhegan Island, a remote spot off the coast of Maine. At one point, she was painting seascapes for tourists to make ends meet.

“I knew there would come a time when this would happen,” said Michael Rancourt, the owner of Ms. Drexler’s estate. “But I didn’t know what the extent would be.”

Two New York galleries are working together to mount a joint exhibition that opens this week: “Lynne Drexler: The First Decade” is the first solo show of Ms. Drexler’s work in the city in 38 years.

The show, running Oct. 27 to Dec. 17, is a mix of works that are for sale and those only on loan; some in each category are from the estate. Mnuchin Gallery, on the Upper East Side, will concentrate on the period from 1959 to 1964 with works that include “Rose Nocturne” (1962), dominated by pink shades.

Berry Campbell, which represents the artist’s estate, will show works at its Chelsea gallery that were made from 1965 to 1969. They will include “Smoked Green” (1967), a piece that shows her abstract work moving toward more defined blocks of color, a direction that picked up speed over time.

Ms. Drexler’s work is back at auction this fall, too, with “Tropical Calm” (1963) going on the block Nov. 18 at Christie’s, estimated at $60,000 to $80,000.

“It feels like a true rediscovery,” Sukanya Rajaratnam, a partner at Mnuchin, said of the artist’s renaissance. “Sometimes there are artists who are hiding in plain sight.” She noted that it was relatively unusual for a backward glance to produce such interest today. “Not every forgotten artist deserves to have their story told,” she said.

Among those who do merit it, “there’s a resurgence of women artists right now,” said Christine Berry, Berry Campbell’s co-founder, noting that women and overlooked artists from the mid-20th century were the focus of her and Martha Campbell’s gallery.

“We’re all interested in being more inclusive about who we add to the canon,” Ms. Berry added.

In the case of Ms. Drexler, a reputational rescue by the marketplace has an irony at its heart. “She hated the art world,” said Tralice Bracy, formerly a curator at the Monhegan Museum in Maine who organized a show of Ms. Drexler’s work there in 2008.

That enmity stemmed from having a promising career derailed. Ms. Bracy, a former Monhegan resident who got to know Ms. Drexler in the last years of her life, met her around 1994 when a friend said, “‘You should meet this artist, she’ll be in the books someday,’” Ms. Bracy recalled.

Ms. Drexler’s experiences were reflected in the paintings and enriched them, she added. “When you look at her life’s work, you see the humanity,” Ms. Bracy said. “They are lyrical, joyful, intense paintings. And then her life gets more complicated.”

Raised near Newport News, Va., Ms. Drexler received a fine arts degree from the Richmond Professional Institute and later went to New York to study separately with two influential painters of the age: Hans Hofmann and Robert Motherwell. Though unknown at the time, she was in the thick of the action among downtown artists.

“She mingled at Cedar Tavern,” Ms. Rajaratnam said, referring to the watering hole of Jackson Pollock and other avant-garde artists.

After much painting and networking, she got her first solo show in 1961 at the prestigious Tanager Gallery, a co-op whose members included Willem de Kooning and Alex Katz. But she did not sell any of the works. That year she met a fellow painter, John Hultberg (1925-2005), whom she married in the spring of 1962, beginning a tumultuous relationship with that better-known artist.

When Mr. Hultberg’s dealer, Martha Jackson, helped him buy a house on Monhegan Island, 12 miles off the coast of Maine — partly as a respite from the art world and the heavy drinking he was struggling with — it became a getaway place for the couple, and later their full-time home.

As the two moved around the country, teaching and showing their work, Ms. Drexler had some sales and good reviews. They settled back in New York in 1967.

“Sure, she was overshadowed by her male contemporaries — that’s how this story goes,” said Sara Friedlander, the deputy chair of postwar and contemporary art at Christie’s, who worked on the spring sales that brought big prices for Ms. Drexler’s work. “But I want to complicate this idea that she was overlooked. She had some commercial success as an artist, and how many people can say that?”

Health problems, Mr. Hultberg’s alcoholism and a changing art world frayed the couple’s relationship, and they moved to Monhegan full time in the early 1980s, separating soon after.

“Life was falling apart,” Ms. Bracy said. “They couldn’t afford the city anymore. They were kind of exhausted.”

But Ms. Drexler never stopped painting.

“She couldn’t get solid gallery representation, but she made art every day and persevered,” Ms. Berry said.

When Ms. Drexler died in 1999, stacks of paintings were found in her house. Mr. Rancourt said that the estate included many paintings and works on paper from the 1950s to the 1990s. “She was an avid painter,” he said. “There are enough works to keep me busy for the rest of my career.”

The early abstract works seem to be gaining more interest in the marketplace, he added, “but she got better as she went along.”

In the 1990s, when Ms. Drexler was living on her own as a full-time resident of Monhegan, her work followed a course that had begun in the previous decade, more clearly depicting real things — landscapes, tabletop items — in a highly stylized way.

“She produced a late group of upbeat representational pictures in warm palettes that manage to transcend their ordinary subject matter and morph into quite captivating compositions,” wrote the art historian Gail Levin in the catalog for “Lynne Drexler: The First Decade.”

Ms. Bracy said she thought she knew how Ms. Drexler would feel about being appreciated anew: “She would be giddy.”

Back to News