From the Mayor's Doorstep: Darby Bannard's Annus Mirabilis: See First. Name Later. at Berry Campbell

June 19, 2022 - Piri Halasz

Here I am, back in the land of the living. Still not sure whether or not I'll be able to maintain my previous pace, but meanwhile here's a review of the current & frankly beautiful show at Berry Campbell – which is "Walter Darby Bannard: See First, Name Later: Paintings 1972-1976" (through July 1).

The middle part of this tripartite title is a quotation from a slender book by Bannard recently published by Signature 16, an imprint of Letter 16 Press of Miami The book is "Aphorisms for Artists: 100 Ways Toward Better Art," and I plan to review it on another occasion, but this review is about Bannard's show, whose 16 pictures are both stunning and classically serene.

MORE BACKGROUND THAN YOU REALLY NEED

Before these paintings were made, Bannard (1934-2016) had been reasonably well-known within the art world, having appeared in two of the biggest and best-publicized group shows of abstract art in the '60s: "Post-Painterly Abstraction" (1964), organized by Clement Greenberg for the Los Angeles County Museum, and "The Responsive Eye" (1965), organized by William Seitz for the Museum of Modern Art.

However, the Greenberg show didn't include only those younger and/or lesser-known '60s painters – like Kenneth Noland and Jack Bush – whom the critic had made a point of celebrating. Rather, it was a huge grab bag of '60s abstract painters of every kind whose sole common denominator was that instead of using the loose brushwork that had been employed by most (if not all) of the first-generation abstract expressionist painters in the '40s and '50s they were creating "hard-edged" images.

(This trait they shared with figurative pop artists of the '60s like Warhol and Lichtenstein, who were getting far more publicity. I have long suspected that this show was Greenberg's way of showing that abstract artists of the '60s were as radical stylistically as pop – hence deserving the same attention. "Style" to him was always the key element. "Subject matter' -- or lack of it -- was beside the point. But I digress.)

Similarly, the Seitz exhibition was a grab bag. It was intended to feature '60s paintings so "hard-edged" that they played tricks with the vision of their viewers, but only some work in the show was truly tricksy. Bridget Riley and Richard Anuszkiewicz, whose work did fit that category, soon became known as "op artists" ("op" being a term coined by my predecessor as writer on art for Time, Jon Borgzinner). But the show also included artists like Noland and Bannard whose work wasn't tricksy at all, and would go down in history as "color-field" painters or "modernists" instead.

THE MOMENT OF TRUTH

During the '60s, though, Bannard's paintings had been minimalist, not "modernist," bland in color and not only hard-edge but also geometric in composition. Only in the early '70s did he loosen up and create more fluid, painterly and coloristically close-valued pictures.

Such pictures would make him one of the top artists most intimately associated with Greenberg. They would also make him a leader among the far larger number of yet younger painters who shared Greenberg's taste for the again-painterly and -- more importantly, coloristically close-valued --- pictures of Jules Olitski.

This meant that Bannard became better and better known within the Greenbergian community -- while slipping from the sight of all those "trendier" observers who couldn't see beyond the charms of pop and its intimate ally, the more familiar minimal.

It's in this context that the paintings of the current show were created – a context in which Bannard was abandoning the relatively popular and familiar in order to strike out in a new and more perilous direction. This must have taken courage – a lot of courage – and I think that's what's incorporated into "See First; Name Later."

Although I didn't become acquainted with Bannard's paintings until the 1980s, his work from the '70s and that of the '80s form a continuum that made me feel at ease with the work in this show. I have never felt that way with Bannard's earlier minimalist work – but with this show, I had a feeling of at last coming home.

NOVEL TECHNIQUES

At the beginning of this most revolutionary period of his career, Bannard was applying paint using diapers instead of brushes and/or closing off areas of his canvases with masking tape. So says Franklin Einspruch, former student from Bannard's later years at the University of Miami in Coral Gables, keeper of the online archive of writings by and about Bannard, and editor of Aphorisms for Artists, in his "Afterword" to that book.

Three of these very experimental works from 1972 are on view here: the still somewhat-tentative "Sampson" and "Westminster," hanging at the very back of the gallery, in a small area seemingly devoted to the thrill of discovery, and "Sometime," a miniature symphony of off-whites measuring only 14 x 10 inches and hanging on the outside wall, just to the left of the door leading to the street.

By the mid '70s, though, Bannard had discovered the joys of applying paint (and occasionally gel) with squeegees. Especially the paintings here from the later '70s display his mastery of this humble tool. (Lisa N. Peters, in her catalogue essay to this show, says only that he used "squeegee-like tools," but Einspruch, himself a painter, says flat-out that these were squeegees.

(Although squeegees may be more often associated with garden-variety housekeeping --as workmen's tools for window-washing and floor-scraping, they come in a wide variety of shapes, sizes and forms, and are part of many artists' toolkits -- as they are widely used in studios in the making of screen prints).

THE SHOW ITSELF

Regardless of their actual dates and the actual tools employed, almost all of the paintings in this show hang together in seamless collegiality. They are grouped together in ways that show common sweeps and coils of shape as well as contrasts in dominant and close-valued color.

This canny juxtaposition continues throughout the show. The first large gallery space is devoted to three fine pictures in a paler spectrum. Facing the street is the vertical, putty-colored "Morning in Detroit" (1974); on the west wall is the large, nearly square and reddish yellowy "Yucatan" (1973), and with its back to the street is the grayish vertical "Vanadium" (1976), with turquoise and purple accents.

The space adjoining this space has mostly darker, mellower pictures, among them "Calico Bend" *1976), "Dakota Run" (1976), and the small but monumental "California Rambler" (1976).

Still, the most significant layout is the one that first greets the visitor upon entering from the street. In addition to "Sometime," with its startlingly early date, two other paintings share this area: "Dover Down" (1973), on the east wall, to the left of the entry, and "Cairo Passing" (1975), facing the entry. The former is built around pale, buttery browns and tans, and the latter, around vaguely grays and blues.

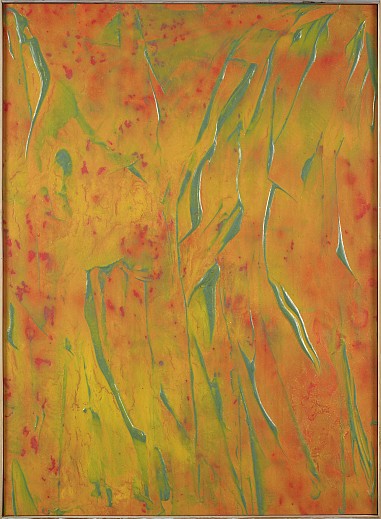

If, however, the visitor makes a hard right, s/he sees the mostly-light-red "Glass Mountain Fireball" (1975).

Hanging high and highly visible over the receptionist's desk, this painting indeed glows: its fundamental red ornamented with accents of green and yellow. One can see how the image resembles a ball of fire. Yet I don't for a moment believe that the artist was trying to depict such a subject.

Like all passionate abstractionists, he had no subject at all in mind when he started to paint this picture. Only dafter it was finished did he ask himself what he was reminded of by it. In other words, he was following the dictum laid down by this moving exhibition's aphoristic title: "See First, Name Later."

Back to News