Frederick J. Brown | Museum showcases retrospective of African American art

November 25, 2021 - Jackie Lupo for The Rivertowns Enterprise

The Hudson River Museum is presenting an important survey exhibition, “African American Art in the 20th Century,” that was organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum and includes 43 objects from their permanent collection.

The show, on display through Jan. 16, 2022, presents paintings and sculpture by 34 African American artists who became famous in the decades between the Harlem Renaissance and the civil rights movement. The works reflect the artists’ responses to the evolving international aesthetic movements of the 20th century, as seen through the lens of race in America. As one of these artists, Jacob Lawrence, said in 1951, “My pictures express my life and experience… the things I have experienced extend to my national, racial and class group. I paint the American scene.”

HRM director and CEO Masha Turchinsky called the Smithsonian’s collection “one of the most significant national collections of African American art. This is a pivotal opportunity for the public to experience powerful works by these American luminaries at the exhibition’s only New York venue.”

The African American experience as shown by these artists embraced both rural and urban life.

In 1940, William H. Johnson, a native of South Carolina, painted “Sowing” in oil on burlap. He used brilliant colors and the naive style characteristic of many of his paintings of country life in the South in the early 20th century.

But the rural South could also be inhospitable for Black people. At first glance, Norman Lewis’ 1962 “Evening Rendezvous” seems largely abstract. Blink, and a sinister scene appears: a crowd of white-hooded Klansmen milling around a red-hot fire. According to the Smithsonian’s label for this painting, the abstract-art-obsessed critics of the time debated whether Lewis meant to make a political statement with this painting.

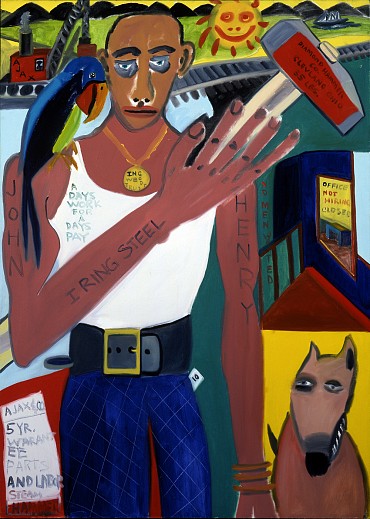

Frederick Brown chose John Henry, a freed slave who was a hero of American folklore and protest music, as the subject for his 1979 oil painting. Brown himself grew up near the steel mills of South Chicago, and his portrayal of Henry is a comment on the contemporary concerns of American laborers.

Cities figured prominently in the Black exodus from the South, but life wasn’t always easier there. The artistic trope of the “portrait of an artist in his studio” is turned on its head in Palmer Hayden’s 1930 oil, “The Janitor Who Paints.” A Black janitor, whose basement apartment is strewn with the tools of his maintenance trade, takes a break from that job to don a jaunty beret, as he goes to his easel to work on a portrait of a mother and child. In real life, Hayden had to support himself as a janitor in order to paint, as did a friend and fellow artist, Cloyd Boykin.

The inner city is also the setting for Beauford Delaney’s 1946 oil painting, “Can Fire in the Park.” Wielding the paintbrush in post-Impressionist style to create a patchwork of vivid colors, he depicts a typical city corner with street lamps, signs, and a manhole cover. Six men, possibly homeless, huddle around a trash can to warm their hands.

Cities continue to fascinate and repel Black artists. But the mood of Charles Searles’ 1975 panoramic acrylic, “Celebration,” is exuberant. It could be a street festival in the artist’s hometown of Philadelphia, but was clearly influenced by the artist’s earlier trip to Nigeria. The canvas is alive with vibrant patterns and textures evoking the textiles of Africa.

A different kind of muralist was Purvis Young, whose 1988 untitled acrylic painting depicts horses surrounded by a frame of abstract rectangular designs. Young, a native of Miami, was a self-taught urban artist who began painting on scrap lumber scavenged from the inner-city neighborhood where he lived, often attaching his paintings to the boarded-up fronts of abandoned buildings.

Thornton Dial’s 1992 mixed-media painting, “Top of the Line,” combines enamel, unbraided canvas roping, and metal on plywood. This emotional, frenzied work was Dial’s response to the Los Angeles riots of 1992, when looters ran amok after a jury found four white policemen not guilty of beating an unarmed Black motorist, Rodney King.

The exhibition also includes sculpture. Sargent Johnson’s 1930s copper sculpture on a wood base, “Mask,” was one of many masks he created. Some were faithful to old African designs, and others depicted people with contemporary American hairstyles, but all were clearly designed to capture the natural beauty and dignity of his race. One also has to wonder whether his interpretations of African masks was an ironic comment on European artists, such as Picasso, who appropriated native African masks and related imagery for profit.

The exhibition’s catalog, “African American Art: Harlem Renaissance, Civil Rights Era, and Beyond,” celebrates modern and contemporary artworks in the Smithsonian American Art Museum collection by African American artists. It will be available in the Museum Shop. Extensive biographical information on all the artists in this exhibition can also be accessed by searching for an artist’s name on the website of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

The Hudson River Museum is located at 511 Warburton Avenue in Yonkers. Museum hours are Thursday–Sunday, 12–5pm. All visitors 12+ must show proof of full vaccination or a negative PCR test taken within 72 hours of visit; those 18+ must also show proof of identity. Visitors under 12 may enter only if accompanied by an adult who can show proof of full vaccination or a negative PCR test taken within 72 hours of visit.

Back to News