BIOGRAPHY

1913-2009

MARY DILL HENRY (1913-2009)

In 1982, Mary Dill Henry settled on Whidbey Island, Washington, where she lived alone, deep in the woods, for the rest of her life. Yet, at the same time, she gained a reputation as one of the leading artists in the Pacific Northwest in the Modernist tradition. Since 1980, seven retrospectives of her art have been held in the region, including several museum shows. Among many honors, she received a Flintridge Award for Visual Artists in 2001 and the Twining Humber Award for Lifetime Achievement, from the Artist Trust, in Seattle, in 2006. Her paintings belong to many public collections, including the Seattle Art Museum; the Frye Art Museum, Seattle; the Whatcom Museum, Bellingham, Washington; the Tacoma Art Museum; the University of Puget Sound, Tacoma; the Portland Art Museum, Oregon; the Sheldon Art Museum, University of Nebraska, Lincoln; and the Institute of Design, Chicago, as well as corporate art collections, including Microsoft, Safeco, Ampex, Varian Associates, and Hewlett-Packard. Additionally, in 2022, the Minneapolis Institute of Art acquired a large scale Henry from 1968.

For Henry, such renown was long overdue. The most significant influence on her art occurred in the mid-1940s, when she studied in Chicago with the Bauhaus teacher and visionary, László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946). Living in the Bay area and then up the coast in Mendocino, California, she was always a serious artist, exhibiting her work regularly but keeping a low profile. Becoming divorced in 1966 was liberating for Henry. Breaking free from the constraints of marriage enabled her to leave behind her role as a housewife and focus on her art, although she struggled to make ends meet.

In her work, Henry maintained the utopian ideals associated with Constructivism, as well the principle behind the de Stijl movement, that art and life are inseparable. Her gridded compositions are Mondrian-influenced, while Moholy-Nagy inspired her outlook. In her Artist’s Narrative, she quoted from his Vision in Motion, that “art is the most complex, vitalizing, and civilizing of human actions.”1 For her, abstract art is “art of the mind, art of the inner eye.” She described her career path as one in which, out of the world’s “chaotic visual feast,” she came “to perceive the geometry of all life, from its infinitesimally and small parts to the structure of the universe.” Making her feelings real in her paintings, she sought clarity and order, constructing her images as she would from a piece of architecture. Painting ideas and emotions, her aim was to convey her concept of spirituality, one in which a symbiotic relationship between humanity and the universe becomes visible.2 In her work, she eliminated non-essentials to achieve a beauty of form that transcends the ordinary and gives joy and surprise to the eye. Her contemplative spaces speak to the viewer with energy and insight, while her sense of humor often comes through.

Born Mary Marguerite Dill on March 19, 1913 in Sonoma, California, the artist was the middle of three children in the family of Eugene and Lucy Dill, whose forebears were small farmers. Mary spent her early childhood in Lake County, where her father owned a small quicksilver mine. When Mary was six, the family moved to the town of Calistoga. In 1928, they settled in Los Altos Hills, where her father was the foreman of Shumate Ranch. Across the road was the fruit ranch owned by the father of Wilbur Henry, Mary’s future husband. An art teacher at Palo Alto High School noticed Mary’s drawing skills and encouraged her to attend art school. Following this advice, she enrolled at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, where her teachers included modernists Ethel Abeel, Glen Wessels, and Marie Togni. The Great Depression was then underway, and Mary paid her tuition by working as a cook maid in private homes, as a cabin maid in Yosemite National Park, and by working on occasion for the California Federal Arts Project in Oakland. She graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in 1938, and that year showed her work at the Oakland Art Museum annual. After studying lithography with Ray Bertrand, she entered her lithograph, Design on a Hill, in a competition. There it caught the eye of the head of Iowa State University’s art department, and she was offered a position teaching applied arts in the home economics department at the Ames campus, where she worked until 1943. Her lithographs of this period primarily depict landscape subjects, rendered with precise stipple-like draftsmanship in a style of rhythmic, simplified stylization, similar to that of Thomas Hart Benton. In lithographs and watercolors, she captured the California hills and towns settled into coastal ranges in a West Coast manifestation of American Regionalism.

In 1940, before leaving for Ames, Mary and Wilbur were married. In 1942, after earning a degree in biology from Stanford University, Wilbur enlisted in the Army, where he served in a Malaria Survey Unit. In 1944, Mary returned to California for the birth of her first child, Suzanne. There she was employed as a draftsman for Bill Hewlett and David Packard, who had started their firm together after meeting at Stanford. That September Mary’s Beach Figure was included in the annual of the San Francisco Museum of Art.

Despite being a new mother, in the following year, Mary pursued her passion triggered by a lecture she had attended in the summer of 1940 at Mills College in Oakland. It had been given by Moholy-Nagy, the Hungarian-born artist who initiated the School of Design in Chicago in 1939. In 1945, Wilbur was still in the military, and Mary took her mother and daughter to Chicago. There she studied with Moholy-Nagy, whose school had by that time come to be known as the Institute of Design (now part of the Illinois Institute of Technology).3 A progressive and idealistic thinker on the cutting edge of many fields—including art, photography, commercial and stage design, and art education—Moholy-Nagy advocated a Constructivist view that new forms of art could serve the public. His perspective was shaped by his role at the center of the Bauhaus at its origins in Germany. He taught at the Bauhaus school in Weimar, from 1923 to 1925 and moved with it to Dessau in 1925, before resigning in 1928, along with the architect Walter Gropius. He then returned to Berlin and subsequently relocated to other European cities, keeping just one step ahead of the Nazis. In 1937, when he emigrated to the United States, his work was featured in the Nazi-organized Degenerate Art Exhibition in Munich. Study under Moholy-Nagy exposed Mary to the illustrious history of the movement and its many manifestations, and at the Institute, she pursued the full Bauhaus curriculum, receiving training in photography, architecture, and design. She recalled that Moholy-Nagy was “so vital” and “exuded magnetism,” commenting: “[He] made you see what abstract non-objective painters were getting at.”4 Of his tutelage, she stated: “He was amazing. He talked about art that wasn’t what you saw, but what you believed. It was like a whole new world opened up for me.”5

In 1946, Mary graduated from the Institute with her Masters in Fine Arts. Shortly before Moholy-Nagy’s death from leukemia in November of that year, he invited Mary to join the institute’s faculty as an associate professor. She was the first woman to be given such an offer. She was also offered a teaching position in the architecture department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Her career was on the upswing at the time. In 1943, she had been included in exhibitions on both coasts, at ACA Gallery in New York and again at the San Francisco Museum of Art. In 1948, she was featured in a show at the Harvard University School of Architecture. However, like many women of her generation who yielded to their husbands’ ambitions, when Wilbur—who had attained a Masters in biology from Harvard University—was hired to work in malaria research and control with the Department of Health in Arkansas, she moved with him first to Bauxite, and later to Helena. In 1947, the couple’s son, William, was born in Little Rock.

Two years later, the family returned to Los Altos Hills, where Wilbur had inherited his family’s fruit ranch and began a job at Lytton Industries in Palo Alto, where he would remain until retirement. For Mary, the years in Arkansas had been a “dark time” and she was overjoyed to return to the California countryside of her youth. In 1952, she won first prize in the McCall’s magazine “Design Your Dream Kitchen” contest, which required contestants to submit detailed plans that included everything from cabinetry to dishes. “Before” and “after” pictures were published in the issue, which appeared in the July 1952 issue, revealing her modern and streamlined aesthetic. From 1950 to 1955, she was a member of the Sign, Scene, and Pictorial Painters Union (local 510).

Between 1953 and 1955 Mary worked for Don Clever’s commercial art firm, which involved commuting five days a week from Los Altos Hills to San Francisco. Her wide variety of assignments included murals for the bar at the Sir Francis Drake Hotel and the Emporium’s Mezzanine Restaurant (both in San Francisco), but as Clever’s employee she was unable to sign her own name to any of them.

In 1955 Mary drew on her professional contacts to start Architectural Arts, a business specializing in large-scale murals and mosaics. The firm produced a series of murals depicting coffee growing for Manning’s Coffee House restaurant in Los Angeles, a mural for the Santa Clara County Courthouse, mosaic walls for two banks in Palo Alto and, most notably, a mural and mosaics for the headquarters of Hewlett-Packard. Architectural Arts also created a small mural and menu design for the Mark St. Regis hotel, several mosaics for private homes, and a lobby sculpture of trees hung with glass “jewels” for the Jack Tar Hotel in San Francisco.

During this period in her art, Mary became committed to using the language of geometric abstraction and its relationship to architectural form in the manner of the Bauhaus. In 1964, she produced watercolors, cross-hatched with pen and ink, that evoke the playfulness of the work of Paul Klee, who had also been a Bauhaus teacher.

In 1960, with $8000 she had earned, Mary purchased a large Victorian house in Mendocino—a coastal town about 150 miles north of San Francisco—and began a process of gradually fixing it up. In 1962–63, an unexpected family windfall enabled her to spend a full year in Europe “to look at art in as many museums and galleries as possible.” At the time, she “thought a lot about the whole thing and decided to drop my whole way of living in Los Altos Hills and to move to Mendocino and concentrate on painting.”6

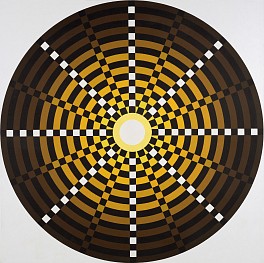

On her return from Europe, Mary moved to Mendocino, which was beginning to attract artists. After she and Wilbur divorced in 1966, she was finally able to pursue her passion for art. In Mendocino, although she had few opportunities to exhibit her work, she had the space and freedom to create large canvases. To support herself, she turned her home into an inn, and eventually sold it. By the mid-1960s, her stylistic trajectory coincided with the Op Art movement, which was at a peak in 1965, when the Museum of Modern Art opened The Responsive Eye. The show presented works of art “less as objects to be examined than as generators of perceptual response in the eye and mind of the viewer.”7 In works of this time, Henry used oscillating shapes in kinetic patterns. Their daringly juxtaposed colors arrest the eye with the immediacy of Pop Art. In Mendocino, when Mary showed at the Heritage House in 1967, her acrylics were deemed in “the class of ‘op art.’”8 That year, she created her On/Off paintings, featuring round-shaped canvases that, with a touch of humor, appear to be actual moving targets, their concentric circles projecting and receding, with some seeming to be retreating from the canvas itself. In her 1968 Love Jazz series, two abstract hearts seem to beat together in rhythmic unison, in time with the variously striped patterns that both unite and divide them.

Henry’s first solo exhibitions were in 1967 and 1968 at the Ampex Corporation, in Redwood City, California, an electronics company that was a pioneer in sound recording. In the summer of 1969, her first gallery show was held at Arleigh Gallery in San Francisco, featuring her On/Off paintings. The show was widely reviewed. In an article in the San Francisco Examiner, titled “It Hurts to Look,” a critic pronounced: “amid her bright designs, her colors are so fluorescent that they sear the viewer’s retina.” Reflecting the audacity of Henry’s work in the context of the era, the reviewer, who found her paintings “uncomfortable to look at” and “trickily restless,” wondered if they were “good art?”9 Among the show’s reviews was one by in Artforum in which Palmer D. French stated that Henry’s pairings of large disc shapes were not obvious, but instead presented “an ingenious and provocative dialogue of syntactical rhythms.”10

Henry’s next solo exhibitions were in 1970 at Sonoma State College, Cotati, California, and in 1971 at Sterling Associates in Palo Alto, where she had participated in several group shows. On view at the latter was her Mendocino Seascape series. Of the show, the Mendocino Coast Beacon reviewer took note of a change that had occurred in her work as she turned seascape forms into “20th Century formal geometric abstractions.” The reviewer stated: “joyous color infuses the artist’s exceptional new work,” while commenting on the humor of some of her titles, such as Clear Except for Isolated Flowers and Rain with the Sun Beginning to Show through a Little Bit.11 In works in the series, she expressed natural phenomena in emotional rather than physical terms. She annotated her drawing for Mighty Clouds with: “Mighty clouds of Joy Come Rolling In.” In the work, the striped shapes, in exuberant flat patterns, span the work’s surface. In Prismatic Rain, teardrop shapes represent a day of steadily falling rain. In Apollo’s Trip, striated lines intersect with the red orb of the sun as it begins its ascent.

Henry adored Mendocino’s “hippie phase,” but when the town became more commercialized, she was ready to move on. In 1974, she traveled to Alaska, where she stayed with a friend’s daughter in Wiseman, on the North Slope, the state’s northernmost borough. There she “experienced such an overwhelming feeling of wilderness, totally cut off from everything except by plane.”12 From the trip, she filled a notebook with sketches that became the basis for her North Slope diptychs, created between 1975 and 1977. In panels measuring four-by-twelve feet that were stripped down to minimalist near-monochromatic rectangles and lines, she responded to the vastness of the glaciers and frozen tundra she had observed.

In 1976, Henry moved to Everett, Washington, to be near her daughter Suzanne, an English professor at Pacific Lutheran University, and Suzanne’s husband, John Rahn, a professor of composition and music theory at the University of Washington. In Everett, she bought three old houses as an investment, living in one and renting the other two. That summer she participated in a master class with Abstract Expressionist Jack Tworkov (1900–1982) at the Centrum Foundation in Port Townsend, Washington. Tworkov said to Henry at the time: “What are you doing here? You obviously don’t need it.”13 However, an outcome of the summer was that Henry developed a kinship with a group of prominent local artists including Lois Graham, Arlene O. Lev, Joan Stuart Ross and Kay Rood. In December 1979, Henry’s son William was killed in a car accident at age 32. The loss was one from which she would never recover.

Her Seattle debut occurred in 1980, when a solo show of her work was held at the Gallery Diane Gilson. Two years later, she sold her Everett houses and purchased an old farmhouse near Freeland on Whidbey Island, Washington. There she transformed her remote surroundings into an English-style picturesque garden and remodeled a woodshed into a studio, while designing and building an extension to the house that she called “the garden room.” During this time, her work became increasingly more influenced by her travels, most notably the gardens of Spain, France, Italy, as well as several countries in the Middle East. In a number of works, she referenced gardens, including the Moghul gardens of Persia, the gardens of Moorish Spain, and of Claude Monet’s Giverny. Her longstanding interest in gardens was also manifested in her own garden on Whidbey Island, which extended well over an acre.

In 1985, a show of Henry’s work was curated by noted Seattle art critic Matthew Kangas at Open Space in Victoria, British Columbia. In 1988, during a period when she was gaining a reputation as a leading Pacific Northwest artist, she was given renewed recognition in California, when a retrospective of her work was held at the Los Altos Hills City Hall. In the same year, she had two solo shows in the Seattle area. One was an exhibition of her large diptychs, organized by the Whatcom Museum, Bellingham, Washington. In a review in Art in America, Kangas acknowledged that Henry was “finally reaping her share of delayed recognition.” He stated: “Looking back to her earlier strictly Constructivist works, one can measure the distance the artist has traveled from a stark geometry to one encompassing irregular, off-center forms and a subtle displacement of symmetrical expectations.”14 The other, held at Pacific Lutheran University, Tacoma, and curated by art professor Richard L. Brown, presented Henry’s paintings and drawings. In the following year, when an exhibition of her work was on view at the Cliff Michel Gallery, Seattle, it was reviewed in Art News. In the article, Lyn Smallwood observed that Henry’s frequent use of bipartite divisions that were “openly warring” carried much of the esthetic weight in her paintings, endowing them with “inherent dynamism.”15

In the years that followed, solo exhibitions of Henry’s work occurred almost yearly, including museum shows in 1992 at the Tacoma Art Museum; in 2001 at the Bellevue Art Museum; in 2005 at the Hallie Ford Museum of Art, Willamette University, Salem, Oregon and at the Schneider Museum of Art, Southern Oregon University, Ashland; in 2009 at the Sun Valley Center for the Arts, Ketchum, Idaho; and in 2017, in memoriam, at Clark College, Vancouver, Washington. From 1992 to 2000, she showed in the annuals of the American Abstract Artists (formed in 1936). In 2004, her work was featured in the exhibition, Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism: Twelve Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington, organized by Marylhurst University in Oregon. The exhibition traveled to several museum venues. In her last years, her work continued to be seen in group exhibitions in museums and galleries. In 2007, a solo show of her work was held at the Howard House Gallery, Seattle, while the private Wright Exhibition Space, Seattle, featured an important installation of her large paintings including diptychs. Exhibitions of works from her estate were held at Jeffrey Thomas Fine Art in Portland in 2015 and 2016, receiving considerable press notice, including a review of the first show in Artforum International, in which Stephanie Snyder described Henry as a “painter’s painter—devoted to daily practice and the slow development of visual concepts over time.”16 In May–June 2020, Elizabeth Leach Gallery, Portland, exhibited Henry’s Prismacolor drawings and vertical T-shaped diptychs created in the 1990s.

During her years on Whidbey, Henry’s art developed in several directions. Rendered from 1985 to 1995, her Striped series conveys a sense of joie-de-vivre, in works that seem related to musical arrangements, featuring ivory-and-ebony piano keys and overlapping rhythms with the complexity and structure of Bach inventions. Recently, Henry’s daughter Suzanne has been helping to create an archive of information on her life and work, to be processed and digitized by Hauser and Wirth Institute.

Her Color of Memory series, produced from 1990 to 2000, consists of deceptively simple works in which figure/ground relationships have an Op art aftereffect. In the Fractured Cubic series of 1994 to 1998, Henry rendered designs based on collages of cut-out shapes, arranged like architectural plans infused with the playfulness of the work of Paul Klee. Henry appropriately used Future as a title for one of these images along with studies for it. A late series, rendered in the late 1990s and early 2000s, consists of elegant geometric patterns that are more complex spatially as well as emotionally than is at first apparent. Mary was also interested in both classical-modern and rock-modern music, at times collaborating with her son-in-law John on music/art works. Such influences are suggested in Music I Heard, 2003, which is vibrantly alive in its retinal energies.

Henry believed that art “sustains us when the chaos of the world with its wars and depressions engulf us.” She felt it is “the bright hope of humanity to know that even in the midst of such hopelessness, we can and do create art that can lift and inspire.”17 Recalled as an artist “of great vision and integrity,” Henry transmitted her responses to life around her in meticulously crafted works of formal clarity and subtle dynamism, carrying the optimism of the Modernist spirit into the twenty-first century.

—Lisa N. Peters, Ph.D.

© Berry Campbell, New York

1Moholy-Nagy’s Vision in Motion was posthumously published in 1947. The quote is from Mary Henry’s “Artist’s Narrative,” 1990, Mary Henry Archive.

2“Artist’s Narrative.”

3For a biography of Moholy-Nagy, see László Moholy-Nagy: A Short Biography of the Artist, a talk by Hattula Moholy-Nagy, University Commons, Ann Arbor, Michigan, Monday, 9 March 2009, https://moholy-nagy.org/biography/, accessed

4Quoted in “Slender, Quiet Freeland Artist Produces Bold, Powerful Murals,” South Whidbey Record, September 24, 1985, p. 6

5Quoted in Sheila Farr, “Mary Henry: 93 Years of Life and Art,” Seattle Times, February 23, 2007.

6Undated holograph, Mary Henry Archives.

7“The Responsive Eye,” press release, February 1965. http://www.moma.org/pdfs/docs/press_archives/3439/releases/MOMA_1965_0015_14.pdf?2010, retrieved August 14, 2020.

8“Gallery Goings On,” Mendocino Coast Beacon, September 29, 1967, p. 14.

9Alexander Fried, “It Can Hurt to Look,” San Francisco Examiner, July 29, 1969, p. 31.

10Palmer D. French, “San Francisco,” Artforum 8 (October 1968), p. 76.

11“Mary Henry Exhibits Mendocino Seascapes at Sterling Associates,” Mendocino Coast Beacon, October 22, 1971, pp. 1, 4.

12Quoted in “Slender, Quiet Freeland Artist Produces Bold, Powerful Murals.”

13Quoted in Matthew Kangas, “Mary Henry: The Last Constructivist,” Art Ltd. (January 2010).

14Matthew Kangas, “Mary Henry,” Art in America 76 (November 1988), pp. 187, 189.

15Lyn Smallwood, “Mary Henry—Cliff Michel Gallery,” Art News 88 (November 1989), p. 178. Stephanie Snyder,” 16Mary Henry,” Artforum International (June 2015), https://www.artforum.com/picks/mary-henry-52932, accessed November 11, 2020.

17“Artist’s Narrative.”

CV

Born 1913, Sonoma, California

Died 2009, Whidbey Island, Washington

EDUCATION

1938 Bachelor of Fine Arts, California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, California 1938-40 Federal Art Project, Oakland, California

1941 San Francisco School of Fine Arts (Studied Lithography)

1945-46 Master of Arts, Institute of Design, Chicago, Illinois

1950-55 Member, Sign, Scene, Pictorial Painters Union, Local 510

1976 Master Painters class with Jack Tworkov, Centram Foundation, Port Townsend, Washington

1981 Monotype workshop with Michael Mazur, Centram Foundation, Port Townsend, Washington

SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS

Arleigh Gallery, San Francisco, California, 1969.

Sonoma State College, Cotati, California, 1970.

Wilkinson/Cobb gallery, Mendocino, California, 1975.

Open Space, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, 1985. (Curated by Matthew Kangas)

Childer/Proctor Gallery, Langley, Washington, 1986.

History Center Archives, De Anza College, Sunnyvale, California, 1987.

Whatcom Museum of History and Art, Bellingham, Washington, Mary Henry: Selected Works, 1988. (Curated by John Olbrantz)

Pacific Lutheran University, Parkland, Washington, Mary Henry: Paintings and Drawings, 1988. (Curated by Richard L. Brown)

Arthead Gallery, Seattle, Washington, 1988.

Childer/Proctor Gallery, Langley, Washington, 1988.

Los Altos Hills City Hall, California, 1988.

Cliff Michel Gallery, Seattle, Washington, Mary Henry: New Constructs, 1989.

Cliff Michel Gallery, Seattle, Washington, Mary Henry/Robert Maki/Al Held, 1990.

Tacoma Art Museum, Washington, Mary Henry, 1992. (Curated by Barbara Johns)

Cliff Michel Gallery, Seattle, Washington, Mary Henry, Non-Objective Works, 1993.

Linda Cannon Gallery, Seattle, Washington, Selected Paintings, 1995.

Meyerson/Nowinski Gallery, Seattle, Washington, The Geometric Tradition in American Art, 1997.

PDX Contemporary Gallery, Portland, Oregon, Mary Henry, Paintings 1968 and 1998, 2000.

Brian Ohno Gallery, Seattle, Washington, Modern Master Works, 2001.

Bellevue Art Museum, Washington, No Limits (Four Wall Mural), 2001.

Bellevue Art Museum, Washington, North Slope Paintings, 2001.

Museum of Northwest Art, La Connor, Washington, In The Gardens of Myth and Logic, 2001.

Lorinda Knight Gallery, Spokane, Washington, Mary Henry, 2002.

Bryan Ohno Gallery, Seattle, Washington, Mary Henry: Select Paintings, 2005.

Schneider Museum of Art, Oregon, Mary Henry: Paintings & Drawings, 2005.

Hallie Ford Museum of Art, Willamette University, Salem, Oregon, Mary Henry: American Constructivist, 2005.

Wright Exhibition Space, Seattle, Washington, Mary Henry Retrospective, 2007.

Howard House, Seattle, Washington, Mary Henry: Paintings & Drawings, 2007.

PDX Contemporary Gallery, Portland, Oregon, Mary Henry: Paintings & Drawings, 2009.

Howard House, Seattle, Washington, Mary Henry: A Life 1913-2009, 2010.

Jeffrey Thomas Fine Art, Portland, Oregon, Gardens of Delight, 2015.

Jeffrey Thomas Fine Art, Portland, Oregon, The Fabric of Space: Select Drawings, 2016.

Clark College, Vancouver, Washington, Practiced Exuberance: Mary Henry, 2017.

Murdoch Exhibition Space, Portland, Oregon, Weight & Movement: The Geometric Inventions Series from 1990, 2018.

Elizabeth Leach Gallery, Portland, Oregon, The Perfection of Structure, 2020.

Berry Campbell, New York, Mary Dill Henry: Love Jazz, 2021.

SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS

Painting Annual, Oakland Art Museum, California, 1938.

San Francisco Museum of Art, California, Annual Exhibition of Paintings, 1941.

Joslyn Memorial Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, 1942.

A.C.A. Gallery, New York, Group Show, 1943.

San Francisco Museum of Art, California, Seventh Annual Exhibition of Drawings and Prints, 1943.

Harvard University, School of Architecture, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1948.

San Francisco Museum of Art, California, Thirteenth Annual Exhibition of Drawings and Prints, 1949.

Ampex Corporation, Redwood City, California, 1967.

Ampex Corporation, Redwood City, California, 1968.

Palo Alto Cultural Center, California, 1971.

Soames-Dunn Building, Pike Place Market, Seattle, Washington, Salon des Refuses 1980, 1980. (Curated by Matthew Kangas)

Gallery Diane Gilson, Seattle, Washington, 1980.

Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, Shapes as Ideas: Abstraction, 1981. (Curated by Harvey West)

Open Space, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, SIZE, A Bumbershoot Visual Arts Exhibition, 1984. (Curated by Matthew Kangas)

Seattle Center, Washington, SIZE, A Bumbershoot Visual Arts Exhibition, 1984. (Curated by Matthew Kangas)

Seattle Center, Washington, Bumberbiennale: Seattle Painting 1925-1985, A Bumbershoot Visual Arts Exhibition, 1985. (Curated by Matthew Kangas)

Childer/Proctor Gallery, Langley, Washington, 1986.

History Center Archives, De Anza College, Sunnyvale, California, 1987.

Seattle Center, Washington, Bumberbiennale: Seattle Sculpture 1927-1987, A Bumbershoot Visual Arts Exhibition, 1987.

Pacific Lutheran University, Parkland, Washington, 1988.

Whatcom Museum of History and Art, Bellingham, Washington, Mary Henry: Selected Works, 1988. (Curated by John Olbrantz)

Arthead Gallery, Seattle, Washington, 1988.

Childer/Proctor Gallery, Langley, Washington, 1988.

Los Altos Hills City Hall, California, 1988.

Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, Illinois, Institute of Design Alumni Exhibition, 1988.

Tacoma Art Museum, Washington, 100 Years of Washington Art, 1989. (Curated by Penelope Loucas)

Center on Contemporary Art, Seattle, Washington, Northwest Annual, 1989. (Juried by Leon Golub and Nancy Spero)

Seattle Center, Washington, Bumberbiennale: Decade of Abstraction 1979-1989, A Bumbershoot Visual Arts Exhibition, 1989.

Cliff Michel Gallery, Seattle, Washington, Mary Henry / Robert Maki / Al Held, 1990.

Washington State Convention and Trade Center, Seattle, Washington, National Governor’s Associations Exhibition of Washington State Artists, 1991.

Portland Community College, Northview Gallery, Portland, Oregon, The Big and the Small of It, 1991. (Curated by Cliff Michel)

Elizabeth Leach Gallery, Portland, Oregon, Abstraction 1: Focus on Form, 1991.

Cliff Michel Gallery, Seattle, Washington, Summer Salon, 1991.

|Tacoma Art Museum, Washington. (Curated by Barbara Johns)

Casa Argentina en Israel, Tierra Santa, Jerusalem, Israel, 1992.

Center on Contemporary Art, Seattle, Washington, Northwest Annual, 1992.

Edwin A Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita State University, Whittier, Kansas, The Persistence of Abstraction, American Abstract Artists 56th Annual Exhibition, 1992.

The Noyes Museum, Oceanville, New Jersey, The Persistence of Abstraction: American Abstract Artists, 1993.

Institut de Artes Visual, Palacio Pombal, Lisbon, Portugal, 1994.

The Linda Cannon Gallery, Seattle, Washington, 1994.

Seattle Center, Modern Art Pavilion, Seattle, Washington, Eyes on Public Work–Seattle City Light Portable Works Collections, 1994. (Curated by Matthew Kangas)

Tacoma Art Museum, Seattle, Washington, Selections from the Northwest Collection, 1994.

Tacoma Art Museum, Washington, 100 Painters, 100 Years, 1995.

CoCA, Seattle, Washington, Folie a Deux, 1995.

Kean College, Union, New Jersey, American Abstract Artists, 60th Anniversary Exhibition, 1996.

Westbeth Gallery, New York, American Abstract Artists, 1996.

PDX Contemporary Gallery, Portland, Oregon, Gallery Artists, 1997.

Meyerson & Nowinski, Seattle, Washington, Drawings… An Annual Bi-coastal Invitational, 1997.

Center on Contemporary Art, Seattle, Washington, Square Painting / Plane Painting, 1997. (Curated by Lauri Chamber)

PDX Contemporary Gallery, Portland, Oregon, Paintings and Drawings, 1999.

Hillwood Art Museum, Long Island University, New York, New York Annual Show; American Abstract Artists Group, 2000.

PDX Contemporary Gallery, Portland, Oregon,Influenced, 2002.

Bryan Ohno Gallery, Seattle, Washington, 5th Anniversary Celebration, 2001.

PDX Contemporary Gallery, Portland, Oregon, Abstracts on Paper and Mixed Media, 2001.

City Space, Seattle, Washington, Variations of Abstraction: Selection from the Portable Collection, 2003.

Seattle Art Museum, Washington, International Abstraction: Making Painting Real, 2003-2004.

The Art Gym, Marylhurst University, Oregon; Museum of Northwest Art, La Conner, Washington; Halli Ford Museum, Salem, Oregon; Schneider Museum of Art, Ashland, Oregon; Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism, 2004-2005.

PDX Contemporary Art, Portland, Oregon, Next, 2005.

PDX Contemporary Art, Portland, Oregon, Mixed Company, 2007.

Oakland Museum of California, California, California College of Art and Craft: 100 Years in the Making, 2007.

Sun Valley Center for the Arts, Idaho, Modern Parallels: The Paintings of Mary Henry and Helen Lundeberg, 2009.

Whatcom Museum, Show of Hands: Northwest Women Artists 1890-2010, 2010.

Jeffrey Thomas Fine Art, Portland, Oregon, Beauty In The Age of Indifference, 2015.

Jeffrey Thomas Fine Art, Portland, Oregon, The Color of Memory, 2016.

Jeffrey Thomas Fine Art, Portland, Oregon, Visible/Invisible, 2017.

Bergdorf/Goodman, New York, Collector Showcase: Dennis Hopper/Mary Henry, 2018.

Sonoma Valley Museum of Art, California, Sonoma: Modern/Contemporary, 2019.

University of Puget Sound, Tacoma, Washington, Works from the UPS Art Collection, 2019.

Frye Art Museum, Seattle, Washington, New Acquisitions, 2019.

Hunter Dunbar Projects, New York, Pt. II: Ninth Street and Beyond: 70 Years of Women in Abstraction, 2022.

Frye Art Museum, Seattle, Washington, In Your Eyes: Experiment Like ESTAR(SER), 2022.

Berry Campbell, New York, Perseverance, 2024.

SELECTED PUBLIC COLLECTIONS

Bogle and Gates, Attorneys at Law, Seattle, Washington

Burma-America Institute, Rangoon, Burma (Myanmar)

Embassy of Argentina, Tel Aviv, Israel

Frye Art Museum, Seattle, Washington

Hallie Ford Museum of Art, Salem, Oregon

Hewlett-Packard Company, Palo Alto, California

Institute of Design, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, Illinois

Kaiser Hospital, Oakland, California

Microsoft Collection, Redmond, Washington

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minnesota

Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art, Utah State University, Logan, Utah

Office of Arts & Culture, Seattle, Washington

Oregon Health Science University, Portland, Oregon

Pacific First Bank, Seattle, Washington

Portland Art Museum, Portland, Oregon

Regional Arts & Culture Council (RACC), Portland, Oregon

Safeco Collection, Seattle, Washington

Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, Washington

Seattle Public Utilities, Seattle, Washington

Seattle City Light, Seattle, Washington

Sheldon Museum of Art, Lincoln, Nebraska

Tacoma Art Museum, Washington

University of Puget Sound, Tacoma, Washington

AWARDS

2006, Twining Humber Award for Lifetime Artistic Achievement, Artist Trust, Seattle, Washington

2001, Flintridge Foundation