Info

Dan Christensen | Late Calligraphic Stains

Feb 9 – Mar 11, 2017

NEW YORK, NEW YORK, January 24, 2017 – Berry Campbell is pleased to announce an exhibition of paintings by Dan Christensen (1942-2007). The exhibition, featuring nineteen paintings from his “Late Calligraphic Stain” period, opens on February 9, 2017 and runs through March 11, 2017 with an opening reception on Thursday, February 9 from 6 to 8 pm.

During his forty-year career, Dan Christensen employed a painting method that involved a considerable amount of improvisation and experimentation.[1] However, his work had a logical and systematic evolution. Using the visual language of abstraction—from Abstract Expressionism through Color Field Painting and Minimalism—he pursued particular lines of inquiry until he felt he had exhausted them. He then changed the variables of his art to move in new directions. Yet, in doing so, he often doubled back, revisiting aspects of his earlier work to rework old themes and create new combinations. Like many artists before him—Picasso and Pollock come to mind—through such recycling, he gave layered resonance to his art.

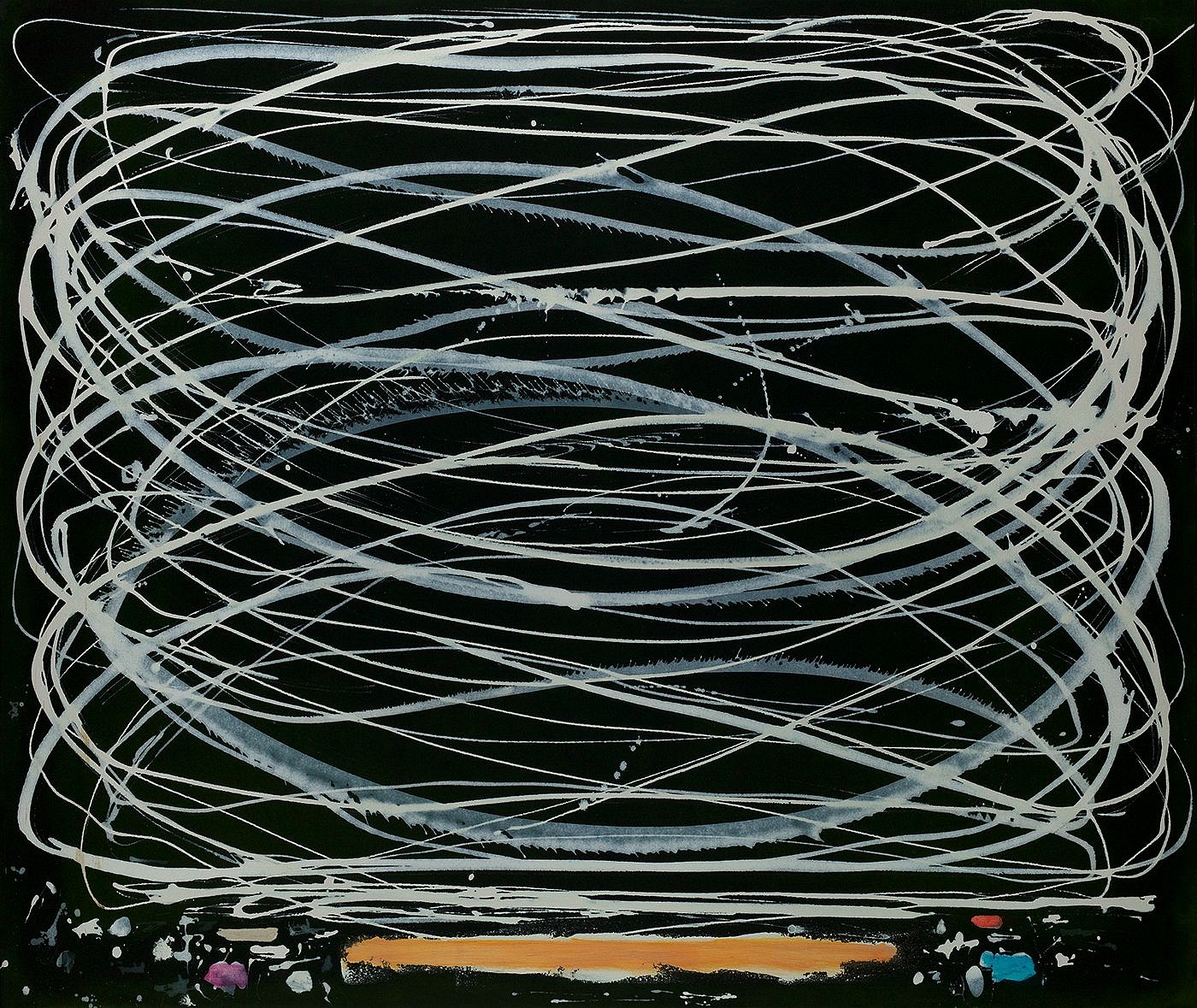

From 1998 through 2006, Christensen rendered a group of paintings that exemplify his process. In these works, known as the “Late Calligraphic Stains,” he turned from the soft-edged floating air-brushed circles that had been the focus of his paintings beginning in 1988 and began to use the methods of staining and “drawing” with pressure sprayers, spray guns, and turkey basters that had characterized a group of works he rendered from 1976 to 1988.[2] This second iteration of stains would constitute some of Christensen’s last works—he died prematurely at age sixty-four in January of 2007. He may not have known that his life would be cut so short, but the paintings in this series reflect his mature vision. While summarizing aspects of his earlier sprays, he turned from their more elusive, shy, and lyrical aspects to a stronger, purer articulation of form and color and a broader emotional range.

The vibrancy of these works is notable, reflecting a time when Christensen and his wife the sculptor Elaine Grove moved permanently from New York City to Springs, East Hampton, New York (previously only their summer home), and he began to work in a new, larger studio that they built at the time.[3] As in his earlier stains, in the late works, Christensen began by laying unstretched canvas on the floor of his studio, stapled to a piece of carpet. He then poured paint onto the surface, spreading it with rollers and then adding additional layers to create toned grounds. In the earlier stains, the staining effects are often evident. Using acrylic paint, the surfaces are pliant, atmospheric, and gently modulated, seemingly lit from within by the presence of lighter tones coming through darker over-layers that at times are thinly applied. In the later stains, such as Saprissa, Western Blues, King’s Point, Tulsa, Chariot, and Morning with Miro, Christensen’s process and layering are not evident. The color is more saturated and stronger, but through his layering, he achieved glowing, soft surfaces rather than hard flat ones. It seems as if he had taken his earlier method and tightened it by making the layering less obvious. When drawn to the patterns of line and shape in these works, we almost forget that the staining is the subject and not merely a background, but Christensen does not seem to mind that figure and ground are no longer in such apparent unity.

Whereas line is part of the compositions in the earlier stains, here the lines have a life of their own. They have become more vital and calligraphic. Christensen manipulated the pressure sprayer with the sensitivity found in the pen work of early Qu’rans or the ink paintings of Zen Masters, varying the shape of the line while maintaining fluidity seen in Finititty and Untitled (2002). He modified the energy of the lines as they progress, at times letting a line dash off as if in a moment of disobedience, impulsiveness, or humor. The shapes formed by the lines probably came into being as Christensen worked, revealing his continued commitment to the idea of painting as process. However, the artist’s personality emerges in the results, which in some cases have a playful aspect. In Western Blues, the darkened atmosphere is awakened by the white calligraphic lines spiraling upward. They evoke streamers and flames and seem to dance and flirt. In Morning with Miro, there is a feeling of tension, between the hourglass verticals, in lavender and sap green, that seem unmoved by the vivacious conviviality of the tangerine and light-red lines that loop vigorously around them. The crimson background adds to the feeling of a heated dialogue.

Although Christensen did not choose a work’s orientation in advance, in several of the late calligraphic stains, he gave his images a gravitational aspect, referencing painting’s illusionistic tradition. The horizontal shapes along the lower edges in Saprissa, King’s Point, and Western Blues make these images suggestive of the sculptures of David Smith, while in their pedestal-like elements, Christensen seems to elevate his type of freeform abstraction into a mode of representation worthy of veneration.

The late stains contain a few in which Christensen merged staining with geometric shapes rendered in a painterly manner with gesso and color accents. In these, including Mandarin Sigh, Ashinto, Ice Tangle, and Japan Blue, he referenced the angularity of his plaids of the late 1960s and early 1970s, but he let the shapes stand out on their own against the stained grounds. In Mandarin Sigh, among his largest works, he created a brushily painted square with a circle inside it at the work’s center, alluding to the ideas of harmony and perfection assigned to these shapes in the classical and Renaissance eras. At the same time, the prominence of the central circle has echoes of Jasper Johns’s and Kenneth Noland’s targets. However, the painting seems more about feeling than perception (as in Johns) or structure (as in Noland). The luminous whites accentuate the cinnamon/orange of the stained surface, while Christensen used color washes on a few side shapes to draw attention away from and then back to the primary contrast.

In the late stains, Christensen united several strands of his art. In one respect, they are thus a culmination. In another, they exemplify his constant process of stretching the limits and possibilities of his mediums, using the vocabulary of abstract painting and his own discoveries to move forward in new directions. While rendered at the end of the artist’s life, they are part of a body of work characterized by ongoing open-endedness.

Dan Christensen was born in Cozad, Nebraska. His father was a farmer and his mother was a schoolteacher. As a teenager, he developed an interest in art on seeing the work of Jackson Pollock on a trip to Denver. Going on to study art, he received his B.F.A. from the Kansas City Art Institute in 1964. He moved to New York that year and was soon recognized as among the new generation of artists who had revived painting after a time when Conceptual Art had been prevalent. Pioneering in his use of spray guns and window-wiper squeegees as artistic tools and in his exploration of the possibilities of latex house paint and recently developed acrylics and their side products, Christensen produced coloristic and surface effects that were innovative and new. The poet and critic John Ashbery included him among a small group of artists who “were extending the language of modernism in a more traditional and serious way.”[4] He described Christensen’s color as “smoldering and sensuous, forcing the eye to recognize distinctions among area of color, which at first have strong family resemblances and only somewhat later turn out to be mavericks who could just as easily be at odds with each other.”[5] In 1990, the important art critic Clement Greenberg would state: “Dan Christensen is one of the painters on whom the course of American art depends.”[6]

Christensen received a National Endowment Grant in 1968 and a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1969. His work has recently been given significant critical and public attention in a solo exhibition organized in 2009 by the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, Missouri. The show was held at the Kemper and at the Sheldon Memorial Museum of Art, University of Nebraska. The present exhibition is the second at Berry Campbell in New York, following a retrospective in October 2015.

Berry Campbell continues to fill an important gap in the downtown art world, showcasing the work of prominent and mid-career artists. The owners, Christine Berry and Martha Campbell, share a curatorial vision of bringing new attention to the works of a selection of postwar and contemporary artists and revealing how these artists have advanced ideas and lessons in powerful and new directions. Other artists and estates represented by the gallery are Edward Avedisian, Walter Darby Bannard, Stanley Boxer, Eric Dever, Perle Fine, Judith Godwin, Balcomb Greene, Gertrude Greene, John Goodyear, Ken Greenleaf, Raymond Hendler, Jill Nathanson, Stephen Pace, Charlotte Park, William Perehudoff, Ann Purcell, Albert Stadler, Mike Solomon, Syd Solomon, Susan Vecsey, James Walsh, Joyce Weinstein, and Larry Zox.

Berry Campbell Gallery is located in the heart of the Chelsea Arts District at 530 West 24th Street, Ground Floor, New York, NY 10011. www.berrycampbell.com. For information, please contact Christine Berry or Martha Campbell at 212.924.2178 or info@berrycampbell.com.

[1] Sources on Christensen include Sharon L. Kennedy, Douglas Drake, and Karen Wilkin, Dan Christensen: Forty Years of Painting, exh. cat. (Kansas City, Mo.: Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, 2009); Lisa N. Peters, Dan Christensen: The Stain Paintings, 1976–1988, exh. cat. (New York: Spanierman Modern, 2011); Dan Christensen: The Plaid Paintings, exh. cat. (including an interview with Elaine Grove) (New York: Spanierman Modern, 2009); and Stephen Westfall, Dan Christensen, exh. cat. (New York: Spanierman Modern, 2007).

[2] On the earlier stains, see Peters 2011.

[3] Christensen and Grove were married in 1978. An actor and model at the time, Grove later became a sculptor. The couple had two sons, Jimmy and Willie. Christensen additionally had a son, Moses, from a first marriage.

[4] John Ashbery, “Pleasures of Paperwork,” Newsweek, March 16, 1981, p. 94.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Clement Greenberg’s statement appears in Dan Christensen: A Survey, 1960–1990, exh. cat. (East Hampton, NY: Vered Gallery, 1990).