ART REVIEW: Raymond Hendler Reveals a Happier Side of Abstract Expressionism

April 12, 2018 - Charles A. Riley II for Hamptons Art Hub

Should an Abstract Expressionist be allowed to be happy? This is the intriguing question asked—and definitively answered—by “Raymond Hendler (1923-1998) | Fifty Years of Painting” at Berry Campbell Gallery in Chelsea, March 15 through April 14, 2018.

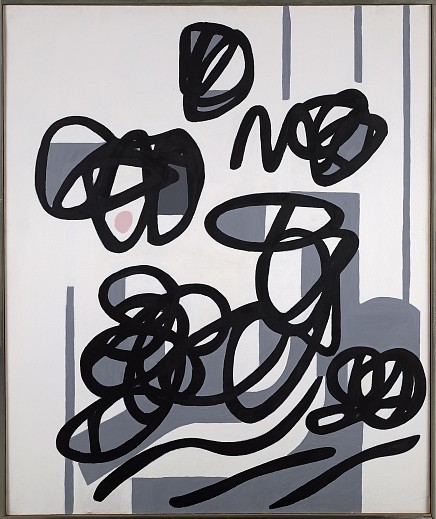

The all-stars of American art’s most fortuitous movement were a notoriously violent and melancholic bunch, wracked with the painful tides of suicides, untimely deaths, divorces and bouts of bitter critical rejection. What a jarringly cheerful contrast Raymond Hendler (1923-1998) presents, with the smiling gestures of his looping black lines and buoyant colors that dash off a jubilant message of confidence and optimism.

Even when he titles one of these acrylic on canvas works Serious and Judicious, the dazzling whites, slate greys and varied blacks (from matte to inky pools) skate lightly across the surface of sensation, leaving the dismal depths of the sublime to those doom-and-gloom purveyors, his lifelong friends Franz Kline (who wrote incisively about Hendler’s work) or the glum Philip Guston. For 50 years, Hendler used bold graphic pictograms as an ingenious, if at times disingenuous, way to keep the bubbles rising in the champagne. It would be hard for a visitor to experience this show without cracking a smile.

The signature of this grinning optimist is his vaguely goofy inscription of RH in more than half the works, the grade-school cursive of the R and plodding timbers of the H insistently presenting his business card to viewers who know perfectly well who he is. I found it comic. Still, looking at Marks of the Renaissance, a mid-career lampoon of the deadly earnest Minimalism of a Brice Marden, seems to require giving Hendler the calligrapher his due. For this reviewer, that meant lingering with the particularly boisterous black on white of Evocative Magic (1979) and the bang-bang group of RH paintings of the 1980s.

With a nod one way to Alexander Calder and Fernand Léger, who loved the graphic design of American advertising and basked in the crass neon of Times Square, and the other way to his heir Roy Lichtenstein, these works play their bright whites and citric yellows to the hilt, exuding an aura of freshness. The main impact, though, is the calligraphy. “Writing is a kind of self-revelation that gives you a chance to become,” the artist wrote, “It acts as a catalyst. It does all a line can do in terms of noting and connoting.” That quote is the key to the show at Berry Campbell.

We would know more about Hendler if he had not spent a chunk of time in his hometown of Philadelphia as a gallerist or teaching in Minneapolis (important examples of his work are at the Walker Art Center). He ran the Hendler Galleries from 1952 to 1954 in Philadelphia, showing not just Kline and Sam Francis but Pollock, de Kooning, Guston and Jack Tworkov. His biography is certainly formidable.

He was a “voting member” of the New York Artist’s Club from 1951 until its demise in 1957, which places him solidly in the first generation of the New York School, alongside de Kooning, Pollock, Milton Resnick and others, alongside as well their stalwart champion Harold Rosenberg. He arrived in Manhattan after two enviable years in Paris, where he parlayed the GI Bill into training at the Academie de la Grande Chaumiere (a real-life version of the fictive artist in John Dos Passos’s “Three Soldiers” who stays in Paris after World War I to learn to paint).

It is important to note the company he kept in France as well as at the Cedar Tavern in New York, because the associations with the Canadian Taschist Jean Paul Riopelle as well as Sam Francies, Al Held, Shirley Jaffe and Jules Olitski seem to have influenced his palette as much as the work of Kline, Guston, Pollock et al. I saw the Riopelle influence particularly in my favorite work in the show, the densely packed (positive space, not recessionary) Number 3 (1951), which delves into the silver, pewter, lead and battleship grays that would later become the natural neutral tones of Jasper Johns.

Hendler also had a strong East End connection: After retiring from teaching in 1984 he moved to East Hampton’s Northwest Woods, where he lived and painted for the last decade of his life with his wife, Mary Rood.

This is the third time Berry Campbell has presented Hendler’s work, and the gallery’s approach is both novel and challenging. If this had been a chronological presentation, the thick gray Number 3that I so admired would have led off, followed by a trio of small, radiant and thickly painted geometric paintings from the late ’50s, in a Rothko-esque palette of oranges and reds. These works predated a major shift in the artist’s composition, which occurred around 1957 when those harder-edged black lines, patches of firm color and childlike floral or cloud forms took over. These are the abstract pictograms that barreled along into the ’80s and which dominate the show with their dynamic, bounding rhythms.

Franz Kline wrote about these later works: “The direct austere design and color complexes paint the image without undue nuances—with clarity and mature independence.” By de-emphasizing the murky early work of 1953, and adhering so closely to the “clarity” that succeeded it, the curators at Berry Campbell have made a particularly strong historical statement. Because I am an art history nerd and like my chronology to be straight, I shuttled back and forth between the back of the long gallery, where the earliest works were paradoxically placed, and the front where the fresh, black on white ideograms were hung in a celebratory display. The effect on my viewing was terrific, because it was Socratic: no passive tour of the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s and ’80s here.

The difference between the earthbound density of Abstract Expressionist surfaces and these floating, Miro-like figures is technically attributable to the attention to white spaces and the solidity of colors. One of the threshold works is a big, pulsing oil on canvas, No. 6, 1959 that the curators did, in fact, place near the front of the show. It has some of the figural grandeur of a Robert Motherwell, but it hints at the earlier hilly terrain of Horizontal – Bryan Liked (No.3) from 1958 or Romulus and Remus of 1964.

It’s not as though Hendler needs apologists. He had major shows in New York, Philadelphia, Minneapolis alongside Marcel Duchamp, Juan Gris, Wassily Kandinsky, Joan Miró and Piet Mondrian. His work is in the Walker, the Philadelphia Museum, and various university museums. Being a happy artist does not make him a lightweight, either. Matisse was a sybarite, and younger visitors to the gallery while I was there were endlessly comparing the jaunty black line of Hendler to the party hardy Keith Haring as well as Carroll Dunham and other Postmoderns.

In a 1902 essay on “The Happiest of the Poets,” William Butler Yeats celebrated “the happiness that is always half of the body.” The poet he referred to was William Morris, and the source of Morris’s joy was the endless and sustainable abundance of natural beauty. Some of that same plenitude is the reassuring, comic basis for this rewarding show.

Back to News