The Artful Life: 5 Things Galerie Editors Love This Week - From a must-see art and design exhibition in Bridgehampton to a gorgeous rug collection by Galerie Creative Mind Avram Rusu

August 2, 2023 - Galerie Editors for Galerie Magazine

August 2, 2023 - Galerie Editors for Galerie Magazine

August 2, 2023 - Rachel Feinblatt for Hamptons Magazine

Proving that no force is stronger than girl power, Frampton Co and Berry Campbell present Women Choose Women at Exhibition The Barn.

February 8, 2023 - The Baer Faxt

Elizabeth Osborne's Passage, 1971 is highlighted by The Baer Faxt in a recent Instagram post discussing Intersect Palm Springs 2023.

September 10, 2022 - Galleries Now

Berry Campbell presents its first exhibition of paintings and works on paper by Elizabeth Osborne (b. 1936). Elizabeth Osborne | A Retrospective features over thirty paintings and works on paper spanning the artist’s career from 1966 to 2021. The exhibition is accompanied by a 20-page catalogue with an essay written by Robert Cozzolino, Patrick and Aimee Butler Curator of Paintings, at the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Cozzolino writes in the catalogue: “A ghostly figure looking out from a doorway…vividly clothed, sensuous figures posed in sparse rooms; land and sky betraying no brushstrokes, horizons to infinity; supernaturally precise still lifes that stop time; charged explorations of the painter’s studio, the past asserting itself in mirrors; vivid bands of light and color echoing the sounds of the cosmos. Few artists of Elizabeth Osborne’s generation have explored as wide a range of subject matter. Driven by curiosity and an unwillingness to repeat herself, Osborne has frequently shifted working methods to support new directions. Born and raised in Philadelphia, Osborne has been at the center of its art world, a critical figure integral to the city’s cultural identity as an educator and as an innovator in her studio. Her art bears the impact of her time in Philadelphia but transcends place, running with multiple streams of modernism and post-war painting.”

Osborne earned her BFA from the University of Pennsylvania in 1959 while also attending the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia. In the 1950s, professors at PAFA were both stylistically progressive and conservative, and Osborne absorbed and employed this dichotomy by mastering their rigorous techniques, while incorporating avant-garde approaches to paint application. Inspired by contemporaries such as Francis Bacon and Nathan Oliveira, Osborne found affinity in their alternative to Abstract Expressionism. At the same time, traumatic losses she endured from her childhood and into her teens continued to reappear throughout her career. Cozzolino observes her grief as present in unexpected ways: “as figures who seem to be mirages, objects intimately observed but separated from one another as though unknowable.”

In 1972, Osborne had her first solo exhibition at Marian Locks’ gallery, a relationship that would last for fifty years. In works for this show, Osborne laid canvas on the studio floor, observing the tenets of Color Field art by pouring paint directly onto unprimed canvas. Unlike her New York and Washington-based contemporaries however, abstraction was never the goal, and she instead created crisp, clear and clean landscapes in assertive colors. “A lot of new and exciting things came together in these paintings,” she explained. “I was working on a larger scale than ever before in a new medium which was thrilling to use and had a great range. I put aside brushes and oils and worked on unprimed canvas. I wasn’t feeling constrained by [PAFA’s] point of view towards light and form and took liberties with my subject matter. The approach allowed me the freedom to take these forms, rocks, vegetation, water, mountains, and push them towards abstraction. It moved me more into that realm than ever before.” [1]

Throughout the following decades, Osborne’s exhibitions continued to sell out. Yet she never allowed herself or her work complacency. She used the fluidity of paint to create large scale figurative acrylics and oils in the mid-1970s, and later developed a technique using watercolor, in which luminosity and precision are unparalleled. By 2009, she abandoned place, figure, and terrain, creating abstractions that bring “representation to the brink of dissolution.” Color is presented “as light, as space, as itself.” By the mid-2000s, she returned to the figure with solitary depictions of family and friends, some of whom have departed. In these works, she incorporates backgrounds that refer back to her recent abstractions. Osborne shows how she remains “interested in getting a very exciting sort of range of paint, and using thin and heavy areas, and getting a certain psychological impact with the figure itself. A kind of haunting figure. Something that people really will remember and think about.”[2]

[1] Author interview with Elizabeth Osborne, conducted on July 17, 2006, in Philadelphia.

[2] Oral history interview with Elizabeth Osborne, 1991 May 24. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

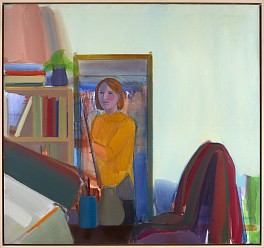

Elizabeth Osborne, Self Portrait in Studio, 1967 Oil on canvas, 56 1/2 x 60 in. (143.5 x 152.4 cm)

September 9, 2022 - Donald Kuspit for Whitehot Magazine

Elizabeth Osborne, Consummate Painter by Donald Kuspit

Elizabeth Osborne: A Retrospective

Berry Campbell

September 8 through October 15, 2022

By DONALD KUSPIT, September 2022

Born in Philadelphia in 1936, and now 86 still living there, the retrospective of Elizabeth Osborne's paintings at Berry Campbell gallery shows the range of her subject matter—she moves effortlessly from figuration to landscape, each work subtly perfected by a deft, nuanced touch, and perhaps above all by her aesthetic mastery of color, but what the retrospective fails to make clear is the psychodynamic import of her paintings, signaled at the beginning of her career by her self-portrait in Black Doorway I, 1966. Standing between a ruthlessly flat plane, its larger upper part pitch black, its somewhat softer, less intimidating lower part oddly greenish, and a canvas, pitch black but with blue paint dripping at its bottom, Osborne conveys a fundamental psychic conflict: between the death instinct, symbolized by the ruthless blackness, and the life instinct, symbolized, however hesitantly, by the green and blue. Osborne herself wears a blue blouse or shirt and black sweater or coat, epitomizing her inner conflict. She stands in a doorway, as the exquisite trompe l’oeil handle suggests, indecisive which door to open—the door to pure abstraction, more or less color field, or the door to figurative painting which she studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Art in Philadelphia, a bastion of figuration since its founding in the 19th century. One might say that Black Doorway I shows her faced with a choice between avant-garde purity and traditional representation. The triumph of her painting, testifying to her creative ingenuity, was their subtle fusion in her paintings after nature, among them the relatively serene—for the redundant streaks of black horizon seem to suggest an impending storm, not to say the death that haunts nature that Poussin famously painted--early watercolor Dana Island Series, 1989 to the rhapsodic, elated Garden Tea Hill 3, 2019, a grandly gestural painting, its colors filled with light.

But to me the painting most telling of Osborne’s mentality, all the more so because she has mastered the personal psychological conflict evident in Black Doorway I without resolving it by projecting it into social space, which neutralizes it by implying that it is universal, even as her presence in The Visit (Two Sisters), 1967 shows that it remains an undecidable dilemma for her. We see her, the white mistress of a house, comfortably reclining on an old-fashioned settee, staring at a young black girl, staring at the spectator rather than Osborne. She may be the painter’s model—the painting resonates with ironical art historical allusions, Manet’s Olympia, 1863 among them, and, perhaps more obliquely and insidiously, seems to allude to photographs of African slaves put up for auction sale—but the social and emotional difference seems the main point of the painting. The painter—for I presume the white woman is Osborne, for her dress is a wonderfully abstract painting, full of the green and brown of nature—seems to be staring at the black woman’s dress—which is white, blue, and pink—as though at another painting, rather than at her brown face. She stands on a green carpet, suggesting she is a creature of nature, like the dog who also stands on it, staring at the spectator. The eyes of the white woman—the artist—and the model—the black woman—and the dog (implicitly the spectator staring at the painting?) do not meet. Connected, they form an oblique triangle, confirming the incommensurateness of their positions and with that their social position, not to say their nature.

The settee is on a bright red carpet, a grand plane that almost encompasses the small green plane—the carpet on which the “native” woman strands, precariously it seems as the fact that she stands on its edge, suggesting the “edginess” of the situation. The two women are hardly sisters, and the visit is not exactly a social call: the native woman is there to serve the artist as a passive model, her arms frozen beside her, fixed to her sides, their inertness and the inertness of her body contrasting sharply with the relaxed, wide open arms, they seem ready to move, and the relaxed pose of the artist, studying her appearance but otherwise not relating to her, not treating her as an intimate friend, but some sort of interesting object. Osborne has sublimated the dilemma, not to say emotional and artistic problem, in Black Doorway I, into a social problem, but the opposites remain, if now in higher, more ingenious aesthetic form, as well as in all too human form. Osborne has mastered the conflict by brilliantly aestheticizing and elaborating and humanizing it, but she states it rather than resolves it, which is to her credit, for it is artistically as well as psychosocially inevitable. What Hegel called the unresolved dialectic of master and slave (or servant)—the unbridgeable difference between one’s (superior) self and the (inferior) Other, as it is called today--is brilliantly rendered, in exquisitely good artistic taste, by Osborne, in effect rationalizing its irrationality, justifying a social injustice.

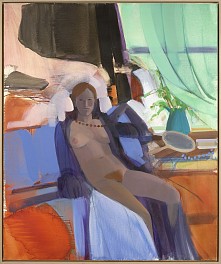

Osborne has painted the female nude again and again, de-sensualizing, de-sexualizing, and de-naturalizing it by treating it as an abstract form, a sum of curves, a sort of arabesque, suggesting the influence of Matisse’s schematic renderings of the female nude—Osborne’s Nude in Blue and Brown, 1989, Nude with Pillow and Nude with Palette, both 2002 are typical—but she seems most at home with nature. Its spreading expanse is more of a challenge because of its variety of forms, nominally together but not holding together, similar but not integrated, the suggestion of disintegration in such works as Floating Islands, 1972-2019, the Dana Island Series, 1989, and Catalina, 2021 more of a challenge than the integrated human body, especially the female body, which has an air of self-sufficiency, self-containment, hermetic insularity. Osborne’s female models are young, beautiful, slim, refined, proudly exhibiting their naked bodies—in sharp contrast to the erratic shapes of the rugged islands, nature uncompromisingly raw and indifferent to the spectator—simply there, more radically naked than Osborne’s female nudes, certainly not appealing to the so-called male gaze as they are, deliberately I would argue because of their exhibitionism. The scattering of islands in the sea, raw forms shaped by it, rising out of it, seemingly spontaneously like the biomorphic Floating Islands, and slowly but surely sinking back into it, as the time-worn Dana Islands seem to be doing, are another symbolic representation of the life instinct and the death instinct, the growing, expanding Floating Islands emblematic of the former, the rotting, shrinking Dana Islands of the latter. Their difference has been Osborne’s theme since Black Doorway I. I think she is more at home with it in her seascapes than in The Visit (Two Sisters), where natural reality is masked and displaced by social reality, however much the artist--the relaxed white woman, full of natural life, as her dress—a sort of artistic second skin--- indicates, while the passive—and impassive--black woman is black as death. They are opposite sides of the same existential coin, reminding me, however obliquely, of the female Fates in classical mythology.

The difference between the Dana Islands and the Floating Islands is as unresolvable as the difference between the resolute abstraction and the uncertain self in Osborne’s Black Doorway I. Her vision of the unresolvable difference—conflict--between life and death has matured, has become more artistically sophisticated—more aesthetically masked--and with that more emotionally manageable than in it is in Black Doorway I, where we see it in all its starkness and rawness. Osborne projects her conflicted self—and conflicted art--into nature, generalizing it as an inescapable truth of being, mastering it by gaining perspective on it—the perspective in her seascapes, in contrast to the lack of perspective in Black Doorway I, where we are confronted by the flat plane and Osborne’s self-representation, both on the picture plane. The seascapes are less upfront, physically and emotionally detached; she is no longer crushed between the Scylla of abstraction and the Charybdis of representation but integrated them in a kind of compromise formation. Osborne’s seascapes are oddly manneristic, for like all manneristic works they make the formal best of a contradiction by bizarrely integrating its terms: her sea is absurdly abstract and absurdly realistic at once, indicating that her art is no longer divided against itself—which is a sign of maturity--as it is in Black Doorway I. WM

September 9, 2022 - Artnet Gallery Network

Every month, hundreds of galleries add newly available works by thousands of artists to the Artnet Gallery Network—and every week, we shine a spotlight on one artist or exhibition you should know. Check out what we have in store, and inquire for more with one simple click.

About the Artist: Elizabeth Osborne (b. 1936) has been painting since the 1950s, and though her name may not be ubiquitously familiar, her career has charted a steady course through the art world decades. In 1959, the Philadelphia-based artist earned her BFA from the University of Pennsylvania while simultaneously attending the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA). At PAFA, she absorbed a rigorous, academic approach to painting that imbued her with a powerful sense of figuration. Beyond the classroom, however, Osborne found inspiration in the boldly gestural works of contemporaneous artists such as Francis Bacon and Nathan Oliveira. In 1972, Osborne had her first solo exhibition with Marian Locks, a gallery relationship that went on to last for some 50 years. In these early works, Osborne laid her canvases on her studio floor, pouring paint onto the canvas—but rather than creating anything akin to the abstract works that dominated the art world at the time, Osborne opted for luminous, mirage-like landscapes. The early singularity of and commitment to her own artistic vision sustained her career over the years that followed. Now New York’s Berry Campbell is inaugurating their new Chelsea gallery space with “Elizabeth Osborne: A Retrospective” a sweeping exhibition bringing together works from the mid-1960s to today, a glimpse into the scope of Osborne’s career.

Why We Like It: Over the decades, Osborne’s paintings have followed an ebb and flow between figuration and abstraction. In works like Reclining Nude with Textiles (1971), she mixes the precision of line in her figurative depictions with bold planes of flat color in her backgrounds. Her embrace of luminous color took in an even more prominent position in her landscapes of the 1980s. By 2009, in fact, she had moved almost fully into abstraction—only to swing back toward representational portraiture by 2015, with figurative images that nevertheless incorporated abstracted backgrounds. Across the decades, her output has maintained an enduringly intimate quality, as though we are glimpsing Osborne’s private world—from portraits of her friends to views from her window—in a way that remains captivating and sincere.

Installation view of “Elizabeth Osborne: A Retrospective,” 2022. Courtesy of Berry Campbell.

According to the Experts: “A ghostly figure looking out from a doorway…vividly clothed, sensuous figures posed in sparse rooms; land and sky betraying no brushstrokes, horizons to infinity; supernaturally precise still lifes that stop time; charged explorations of the painter’s studio, the past asserting itself in mirrors; vivid bands of light and color echoing the sounds of the cosmos. Few artists of Elizabeth Osborne’s generation have explored as wide a range of subject matter. Driven by curiosity and an unwillingness to repeat herself, Osborne has frequently shifted working methods to support new directions. Born and raised in Philadelphia, Osborne has been at the center of its art world, integral to the city’s cultural identity as an educator and as an innovator in her studio. Her art bears the impact of her time in Philadelphia but transcends place, running with multiple streams of modernism and postwar painting,” wrote Robert Cozzolino, curator of paintings at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, in an essay accompanying the exhibition.

Browse works by the artist below.

Elizabeth Osborne, Dana Island Series (1989). Courtesy of Berry Campbell.

Elizabeth Osborne, Statues with Peruvian Weaving (1976). Courtesy of Berry Campbell.

Elizabeth Osborne, Maine Portrait (2016). Courtesy of Berry Campbell.

Elizabeth Osborne, Nightfall (2018–19). Courtesy of Berry Campbell.

“Elizabeth Osborne: A Retrospective” is the inaugural exhibition at Berry Campbell’s new location, at 524 West 26th Street in New York. The exhibition is on view from September 8–October 15, 2022.

September 8, 2022 - Berry Campbell

May 17, 2022 - Delaware Art Museum

Delaware Art Museum, Louisa du Pont Copeland Memorial Fund, partial gift from the artist, and purchased with funds donated by Doug Schaller and David Barquist, Brad Greenwood and Anne M. Lampe, 2022.

February 10, 2022 - Berry Campbell

Now Representing Elizabeth Osborne (b. 1936)

Solo Exhibition Forthcoming September 2022

View Works by Elizabeth Osborne

View Bio and CV

ABOUT THE ARTIST

A ghostly figure looking out from a doorway; actual windshield wipers positioned over a painted car window; vividly clothed, sensuous figures posed in sparse rooms; land and sky betraying no brushstrokes, horizons to infinity; supernaturally precise still lifes that stop time; charged explorations of the painter’s studio, the past asserting itself in mirrors; vivid bands of light and color echoing the sounds of the cosmos. Few artists of Elizabeth Osborne’s generation have explored as wide a range of subject matter. Driven by curiosity and an unwillingness to repeat herself, Osborne has frequently shifted working methods to support new directions. Born and raised in Philadelphia, Osborne has been at the center of its art world, a critical figure integral to the city’s cultural identity as an educator and as an innovator in her studio. Her art bears the impact of her time in Philadelphia but transcends place, running with multiple streams of modernism and post-war painting.

Osborne had a progressive Quaker education at Friends Central School near the original site of the Barnes Foundation. Two mentors in her childhood, Louis W. Flaccus and Hobson Pittman, supported her early drive and talent in art. Flaccus, a family friend, was a professor of Philosophy and amateur painter; Pittman was a professional artist who taught at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) and at Friends Central. Both men encouraged Osborne to defy societal expectations of young women and to trust her passion and instincts for a career in art. Osborne took advantage of everything that Philadelphia offered a young artist. She visited galleries, museums, and took additional classes outside of her school week at the Philadelphia Museum College (now University of the Arts) with painter Neil Welliver. Surviving work from this period shows that Osborne was quick to understand observational drawing, grasping the nuances of form and the emotional capacity of line and color.

These relationships grounded Osborne as she endured a series of traumatic losses during childhood and into her teens. Her father Charles died from leukemia in 1945. Three years later her mother, Virginia, killed herself by overdosing on pills. Osborne and her siblings, including an older brother and a twin sister, were left to be raised by Virginia’s brother and wife. In 1954 while painting a portrait of her grandfather, he revealed that her biological father was the architect, Paul Philippe Cret (1876-1945), who had died the same year as Charles Osborne, further illuminating the impact of loss on her mother. In 1955 her twin sister Anne killed herself while Osborne was traveling in France on a fellowship. These tragedies have resurfaced in her work throughout her career in unexpected ways – as figures who seem to be mirages, objects intimately observed but separated from one another as though unknowable. Osborne has reflected on the impact of grief on her work and how it affected her figure paintings:

"My work really was affected for a while by the loss of loved ones, of the presence of death…In the figurative paintings there’s probably this connection with longing and missing my sister in the solitary figures and the darkness with figures emerging and receding…Losing people is imprinted…there is a natural impulse to have these people back. They disappear from your sight, your life but they reappear when you try to go to sleep at night."[1]

By 1954 Osborne had entered PAFA while simultaneously working towards a BFA at the University of Pennsylvania. At the time, PAFA was a mixture of progressive instructors and conservative academics resistant to many modernist developments of the previous half century. Founded in 1805 and the first museum and art school in the United States, it was an immersive experience for art students, offering a rich permanent collection and annual exhibitions of contemporary American art. Among her instructors were experimental figure painter Ben Kamihira, abstract artist Jimmy Leuders, realists Francis Speight and Walter Stuempfig, and traditional modernist Franklin Watkins. Osborne’s training encompassed working from life models, drawing from casts and still life set ups, and other rigorous beaux-arts-based pedagogy. She maintains that her most fruitful relationships and education came through the camaraderie between friends and fellow students including Raymond Saunders. Continue Reading