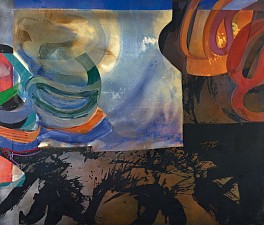

Susan Vecsey, Frank Wimberley | Guild Hall, 82nd Artist Members Exhibition

June 11, 2020 - Guild Hall

June 11, 2020 - Guild Hall

June 11, 2020 - Widewalls

June 10, 2020 - Berry Campbell

In this video, Jill Nathanson gives a tour of her studio in Hoboken, New Jersey, featuring some of her paintings in progress.

Read More >>

May 28, 2020 - Berry Campbell

PRESS RELEASE

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

EXTENDED: SYD SOLOMON: CONCEALED AND REVEALED AT THE JOHN AND MABLE RINGLING MUSEUM OF ART

NEW YORK, NEW YORK, MAY 28, 2020—Berry Campbell is pleased to announce the extension of the Syd Solomon traveling museum exhibition, Syd Solomon: Concealed and Revealed. After opening at the Deland Museum, Florida in 2016, the retrospective traveled to the Greenville County Museum, South Carolina (2017), and then to Guild Hall Museum, East Hampton, New York (2018). The exhibition opened at its final venue, The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota, Florida, in December of 2019. Shortly after a full-day symposium on Syd Solomon in February 2020, the museum temporarily closed due to COVID-19. The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art reopened to the public on May 27, 2020 and will extend Syd Solomon: Concealed and Revealed and all associated programing through January 2021.

Syd Solomon: Concealed and Revealed consists of 45 paintings and works on paper sourced from public and private collections, including hundreds of original and never seen before archival photographs and documents from the Solomon Archive. These newly discovered materials detail how Syd Solomon's World War II camouflage designs and other early graphic arts skills were foundational to his unique approach to Abstract Expressionism. This new information makes this exhibition and accompanying catalogue a revelation by furthering the understanding of Syd Solomon’s life and work.

Syd Solomon served as camouflage expert in the United States Army during World War II (1941- 1945), which prevented him from taking part in the formative years of the Abstract Expressionist movement in New York. His camouflage designs were used during the Normandy invasion and in the African campaign and his camouflage instruction manuals where distributed throughout the US Army. Solomon's designs were shared with the English camouflage experts, many of whom were artists, including Barbara Hepworth, Roland Penrose, and Henry Moore. Syd Solomon was awarded five Bronze Stars for his service.

Solomon suffered frostbite in the Battle of the Bulge and was not able to live in cold climates, thus settling in Sarasota, Florida. Although he arrived to the Abstract Expressionist scene late because of the War, by 1959 his work had gained the admiration of Museum of Modern Art curators, Peter Selz and Dorothy C. Miller, the Whitney Museum of American Art's director, John Baur, and many others, including artists Philip Guston and James Brooks, who became life-long friends. At this time, Syd Solomon's paintings entered the collections of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and over 100 additional museum collections.

This exhibition was co-curated by Mike Solomon, the artist’s son, and Ola Wlusek, the Keith D. and Linda L. Monda Curator of Modern Art and Contemporary Art, at the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota, Florida.

Syd Solomon: Concealed and Revealed is accompanied by a 96-page hardcover catalogue with essays by Michael Auping (former Chief Curator at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth and curator of recent exhibitions of Frank Stella and Mark Bradford), Dr. Gail Levin (expert on Lee Krasner and Edward Hopper), George Bolge (Director of the Deland Museum of Art, Florida), and Mike Solomon, (artist and the artist’s son). This exhibition was organized by the Estate of Syd Solomon in conjunction with Berry Campbell, New York.

For museum hours of operation, please visit: www.Ringling.org. To visit the exhibition virtually, please visit: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0f1b8wRQhsw. To purchase the exhibition catalogue, please email: info@berrycampbell.com.

May 23, 2020 - Vittorio Colaizzi for Woman's Art Journal

Writing in 1981 of paintings made between 1955 and 1962, critic Theodore F. Wolff claimed that the work of Abstract Expressionist painter Yvonne Thomas (1913–2009) “reminds us that good painting is good painting regardless of the form it takes.”1 Wolff’s assertion must make the sober and disinterested scholar a little queasy, but it is typical, if somewhat strident, of criticism of Thomas’s work, in that it combines an appeal to quality with an acknowledgement of historical contingency. In this way it demonstrates the problem that Thomas’s work poses for educated viewers. Criticism of the last half century has tended to homogenize and dismiss gestural abstraction as an embodiment of inadvisably idealistic values, and as a foil to or baseline for the performative, sculptural, or photographic work that repudiated or grew from this kind of painting—consider for example the work of Carolee Schneemann (1939–2019). While painting itself currently enjoys wide and varied manifestations, and claims about Thomas’s sheer quality proliferate, a certain familiar aspect to her abstraction, as is evident in Summer Fantasy (1954; Pl. 1), was noticed in published criticism as early as 1956. This did not prevent Dore Ashton from attributing to her “genuinely fresh insights,” nor Donald Judd from excepting her from his nearuniversal condemnation of gestural abstraction with a positive review in 1960. 2

Born Yvonne Navello in Nice, France, in 1913, she moved to Boston with her family in 1926. She showed an interest and aptitude for art from an early age, and following studies at the Cooper Union began a career in commercial art in the 1930s. She married Leonard Thomas in 1938 (they lived in Newport, Rhode Island, during the war), and maintained close ties with the New York art world throughout her life (Fig. 1). She attended the Art Students League in 1940, and studied with Vaclav Vytacil. She also had private lessons with Dimitri Romanovsky (a Russian artist specializing in nudes and portraiture), and attended the Ozenfant School of Art. Nearly every published account of Thomas’s work mentions her participation in the innovative and short-lived painting workshop entitled “The Subjects of the Artists,” which ran from 1948 to 1949 and was initiated but abandoned by Clyfford Still and taken up by Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, William Baziotes, and David Hare. Barnett Newman joined in the second year. These sessions were an avenue for the five burgeoning Abstract Expressionists to share with an equal number of interested students, Thomas among them, their incipient methods of free painting, bidden by one’s inclinations in the face of the materials and presumably conditioned by the subconscious mind. Ten years later and throughout her life, this sense of freedom remained in her paintings and works on paper, as a small but expansive gouache shows (Fig. 2; 1959).The aim, as Robert Hobbs and Barbara Cavaliere have shown in their landmark 1977 article, “Against a Newer Laocoon,” was to allow a less literary, less illustrative surrealism to take root. 3

In 1950 she enrolled in one of Hans Hofmann’s summer classes, and in the next decade was included in group exhibitions of artists identified with Abstract Expressionism, including those at New York’s Stable Gallery, from 1953 to 1957. The—only relative—belatedness with which Thomas came to Abstract Expressionism, the stylistic variety she pursued, and the nuanced and revealing critical account that exists, together resonate with contemporary concerns about painting’s viability that are rooted in midcentury abstraction and its reception. Continue Reading

May 20, 2020 - Jonathan Goodman for Tussle Magazine

This exhibition titled "Cloistered" by Ida Kohlmeyer at the Berry Campbell Gallery consists of paintings and sculptures from the late 1960s, before she turned to the hieratic abstractions of her later career. In some ways the paintings on show relate to abstract elements found in the art of Georgia O’Keeffe and Hilma af Klint (the early 20th century Swedish abstractionist); they consist of mostly diamond-shaped patterns, with a couple of circular compositions. Kohlmeyer was educated and taught at Tulane University in New Orleans; she studied in Provincetown in the middle Fifties with the German-born teacher and abstract painter Hans Hofmann. In the paintings available to us, we see distinguished, soft-edged nonobjective imagery, in which geometric forms become vehicles for understated emotion. The colors are softly muted, communicating the artist’s ability to transmit feeling through simple designs and quite hues.

While not exactly a serial art, this kind of abstraction builds its effects through repetition of forms from one painting to the next. The diamond-shaped designs hold our interest by building a narrowing focus into the very center of the paintings, which can contain different shapes often circles, but also crosses and slits. They offer a kind of artist’s vernacular; the shapes repeat themselves and create links joining one painting to another. As a result, the body of work joins individual voices to a communal process that asks Kohlmeyer’s audience to appreciate their cumulative effect. Thus, a particularly successful variation within unity occurs, full in keeping with a lot of painting being done at the time these works were made. The larger question, Does such repetitiveness add or detract from the experience of the work? This can be considered as something more theoretical--in the case of Kohlmeyer, the accomplishments brought about by such an approach are genuine, in part because the differences from one painting to the next which are large enough to enable us to see the works as individual efforts rather than as nearly identical compositions.

In “Cloistered” (1969), Kohlmeyer has painted a thin, mostly brown diamond with a thinner dark purple stripe re-enforcing the overall shape, inside of which is another diamond, outlined in white and surrounded by a haze of the same dark-purple color. Inside the confines of the white diamond is a thin, yellow-brown, vertically aligned lozenge, flanked on either side by purple and then dark-brown stripes--the same colors used to define the outer diamond. The title might well refer to the oval deep in the center of the painting; it might even convey something of the spiritual mood that exists in the work. Whatever the motivation for the painting is, the experience of Kohlmeyer’s effort is fully satisfying. It suggests, in abstract fashion, a place of refuge and solace. An untitled work, circa 1969, consists of a five-pointed star shape, within which is a white diamond with a circle in the middle. Outside this puzzle of shapes are found a pentangle of red paint, along with a pink area, following the form of the pentangle in a rough manner, linearly contained by a dark-brown line. Certainly, the star is abstract enough, but the image conveys a primal feeling not unaligned with the spirit.

Kohlmeyer’s shapes can hardly be seen as devotional, yet they are so basic as to be archetypal reworking of forms that may have had spiritual meaning in other, earlier cultures. In “Black Insert” (1968), we see a black diamond shape, in the middle of which is the vertical lozenge; this amalgam of forms is supported by quadrants of off white, defined by green stripes of middling width that outline the diamond. The green lines create a cross behind the diamond that does not in any way evoke a Christian aura.

The possibility of external reference, beyond the abstract form, cannot be entirely dismissed. It would be a major mistake to see the works of art as intimating an atmosphere of piety. It is just that the forms in these completely abstract paintings are so archaic as to raise questions about their origins beyond the intentions of the artist. This happens inevitably. In “Suspended” (1968), we meet more rounded forms: a curving hourglass shape dominates the painting, with rows of undulating, differently colored lines embellishing the upper and lower register of the form. Outside this hourglass is a background of whitish, slate blue curved like a circle. Beyond that, there exists a green diamond, with four pinkish mauve triangles, one in each of the cardinal directions. Finally, a smudged light-yellow band follows the edge of the green diamond.

May 18, 2020 - William Corwin for The Brooklyn Rail

Think of all the meanings, nuances, and implications embedded in the word “cloistered,” and they reside here in Ida Kohlmeyer’s series of that title, executed in the late 1960s and now on virtual view at Berry Campbell Gallery through May 23. The earliest of these works were produced in 1968, the same year Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey came out, and many of them have the wary and watchful quality of the monotonic computer HAL, which loses faith in its human chaperones in Stanley Kubrick’s iconic film.

In Kohlmeyer’s paintings, there is a protected conceptual space lying just below the surface of the canvas, under a layer of sparingly applied oil paint and graphite. This is the imaginary volumetric structure for most of Kohlmeyer’s imagery in this series: a somber interior zone peeks out through a central oculus, or blossoms in an undulating vegetal sprout. The relationship of painting to the viewer is reversed as the spectator is surveilled by an alien eye. Kohlmeyer paints this cloistered presence into her works with varying degrees of directness. Black Insert” (1968) simply presents a black diamond with a lightly incised rectilinear form floating, shadowy, within it. By contrast, the final painting in the show, Cloistered (1969), stares out obsessively from the back of the gallery. A cross is carefully etched on the lozenge of the eye, a detail that makes the viewer feel as if the painting broodingly judges them. Kohlmeyer's reclusive entities carry with them all the accompanying angst, sadness, concealment, and, at times, anger, that arise from an unwilling sequestration.

There’s also a more immediate structural interpretation: most of the works are geometric, but with relaxed hand-drawn lines, and play on the symmetry and proportion of medieval walled gardens—the literal cloister. The picture plane is quartered or in some cases halved, and has a central element that serves as a point of arrival for the vectors of the painting and attracts the eye of the viewer. In this central position, Kohlmeyer typically substitutes something dark and glowering for the babbling fountains and cheerful plantings most of us know from the Cloisters museum in Fort Tryon Park. Of the paintings on view, the most Kubrickian watcher of all is the bisected black cornea and dilated pupil of Cloister #5 (1968). But there are exceptions, and Kohlmeyer does occasionally traffic in less emotionally fraught effects. Cloistered #12 (c. 1969) culminates in a colorful black/blue and pink/yellow floret, while Suspended (1968), with its palette of bright grass greens, iris, and greenish yellow, is very upbeat, and seemingly Easter-themed, including a central egg-shaped form decorated with arcs and bands. Kohlmeyer’s sculptures are variations on the theme of the paintings, but play with the idea of multiplicity. Canvas stretched over wood, they are paintings moved off the wall and placed in space, toying with a front and back in three dimensions. Stacked #1 (1969), is a tower of three cubes, with fecund buds centered on each surface: the painting now overlooks the entire room like a cyborg lighthouse.

There are obvious relationships that can be drawn between Kohlmeyer’s paintings and human anatomy—eyes and other organs are most obvious. But the repetitive crosses and ecclesiastically-specific architectural titles reiterate a spiritual and symbolic subtext that moves beyond mere floral or organic models. It is hard to say what the message is—the works themselves, juxtaposing bright colors with a forlorn presence, may not have decided for themselves. Before she created the works on view at Berry Campbell, Kohlmeyer’s style was Abstract Expressionist, influenced by Rothko and Gorky. The artist also studied under Hans Hofmann in Provincetown in the mid-fifties. Her later work would go on to explore ideas of pattern and multiplicity—Berry Campbell offers a striking example of this period in Color Stripes (1980). The Cloister series and its auxiliary works seem to represent an interlude of sorts, during which the artist explored a closer, but riskier, engagement with the viewer. These paintings have a pathos to them, but never veer into the outright horror or fury of Lee Bontecou’s dark blank lacunae from the late 1950s and early 1960s. As with all series carried out over just a few years, it’s impossible to tell if Kohlmeyer could have continued to walk the fine line between gripping emotional connectedness and over-the-top sentimentality, but for this short span, she certainly pulled it off.

May 14, 2020 - Berry Campbell

In this video, Christine Berry speaks on Abstract Expressionist, Syd Solomon.

Read More >>

May 11, 2020 - Stacey Stowe for The New York Times

The outdoor exhibition on Long Island featured works installed at properties from Hampton Bays to Montauk, with social isolation as just one theme.

No one was supposed to get too close to each other over the weekend during a drive-by exhibition of works by 52 artists on the South Fork of Long Island — a dose of culture amid the sterile isolation imposed by the pandemic. But some people couldn’t help themselves...

There was spontaneous interaction. The artist Bastienne Schmidt, dressed in a bright blue pea coat and red pants, waved to those who checked out her installation of canvas-wrapped posts set six feet apart at the Bridgehampton home she shares with her husband, the photographer Philippe Cheng. Kathryn McGraw Berry, an architect sampling the tour in a champagne-colored Audi, chatted with Eric Dever, who was checking the wind resistance of his 12 paintings mounted on posts at his 18th-century Water Mill home.

“It’s nice seeing one’s work in the landscape when you’ve been cooped up in the house,” Mr. Dever said. “I grew up in Southern California so I appreciate the drive-through idea.”

May 8, 2020 - Robert Passal Interior Design

"#meansformakers Please join us for raising COVID19 relief funds for @cerfplus by sharing a favorite artist or artisan that inspires you. @arteriorshome will donate funds for each of our posts to @cerfplus who will in turn support the skilled artists of the artisans society. Just post your favorite maker’s work and tag @arteriors home and #meansformakers I am sharing several projects showcasing custom pieces done by some of the incredible artisans we continually work with. The work of each of these artisans truly makes each of our projects shine."

View Post on Instagram