AVEDISIAN AT BERRY CAMPBELL: JUST WHAT THE DOCTOR ORDERED

September 26, 2020

By: Piri Halasz

Edward Avedisian (1936-2007) wasn't in "Post-Painterly Abstraction," the landmark show organized by Clement Greenberg in 1962. He is, however, included in "Clement Greenberg: A Critic's Collection," the catalogue of work owned by the late critic and acquired by the Portland Art Museum in 2000. And, like other, better-known color-field painters, Avedisian evidently understood the importance of making beautiful art that can offer balm to the wounded soul even –or perhaps especially -- in the most trying times.

The twelve paintings in this show date from 1963 to 1965. This was a period wracked by Vietnam, the first upheavals of the civil rights movement, and the assassination of JFK. And so this show comes like just what the doctor ordered in this equally if not more messed-up, politically toxic and disease-ridden New York moment of 2020.

Go and feast your eyes on "Edward Avedisian: Reverberations" at Berry Campbell (through October 10). It will let you take a trip for a few brief moments out of the here and now..and will therefore allow you to return, refreshed & reinvigorated, to do whatever you think may need to be done with redoubled zeal.

I confess that Avedisian's name wasn't familiar to me when I walked into this show. With the aid of the gallery's literature (as well as a bit of help from the web) I can report that he was born in Lowell, Massachusetts, and studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. After having had at least one show in the Boston area, he moved to New York in the late '50s.

There he studied a bit more (at the School of Visual Arts), and became involved with the adult New York art scene. He was part of a whole younger generation of abstract artists: near-contemporaries included Darby Bannard (1934-2016), Frank Stella (b. 1936), and Larry Poons (b. 1937). From what l can tell, it seems that Avedisian's initial abstractions were painterly, in the tradition of first-generation abstract expressionism, and only became post-painterly later on.

He had a show in 1958 at the short-lived Hansa Gallery. Though it's not clear to me what kind of work he showed, the gallery was under the direction of Richard Bellamy & Ivan Karp, two live wires on the neo-Dada, pop-art front.

The Berry Campbell literature suggests that Avedisian combined the "hot" colors of pop with the "cool, more analytical qualities of Color Field painting." Certainly, Avedisian's colors are bright, but I don't see any further analogies with the limited and coloristically obvious palette of the likes of Warhol, Wesselman, Rosenquist or Lichtenstein.

Rather, I find most of Avedisian's colors far more varied & sophisticated than pop-art colors—fortunately (as far as I'm concerned).

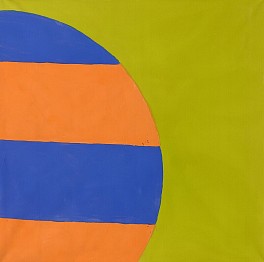

All of these paintings are about circles, and of course circles are richly allusive: they are reminiscent of everything from suns, moon and stars to faces and bouncing balls – even (to be a little anachronistic) emojis.

These shapes are not only allusive but also wonderfully cheerful.

And there seems to be a sort of progression in this show from paintings with two, three or five little balls – decorated in various ways --- to paintings with just one.

The balls in the paintings with one ball in them are striped, like beach balls. The biggest canvas, a majestic horizontal in deep purple, has only a small ball floating near its lower edge – this ball is striped with a lighter purple and orange. It is a very impressive work.

But I guess my real favorites are the ones where the balls grow big, big and bigger, until they outgrow the canvas and only a portion of them can be shown---like the moon coming over a mountain.

There are five of these paintings in all, including one right at the entrance, one in the first gallery space, one (a smaller watercolor) in the central space, and two at the very back of the gallery.

The one I have chosen to reproduce hangs on the southernmost gallery wall. Here the circle has grown so big that only a quarter of it can be shown. The circle has navy blue and lime green vertical stripes, while the field that it dominates is a rich cinnamon brown. And the stripes descend from the top of the painting, making the ball look impossibly large and imposing.

But what is it, really? The moon seen through a powerful telescope? Or the ocean seen through a periscope? The magic of abstraction is it can be all of these – or none.

Read More >>